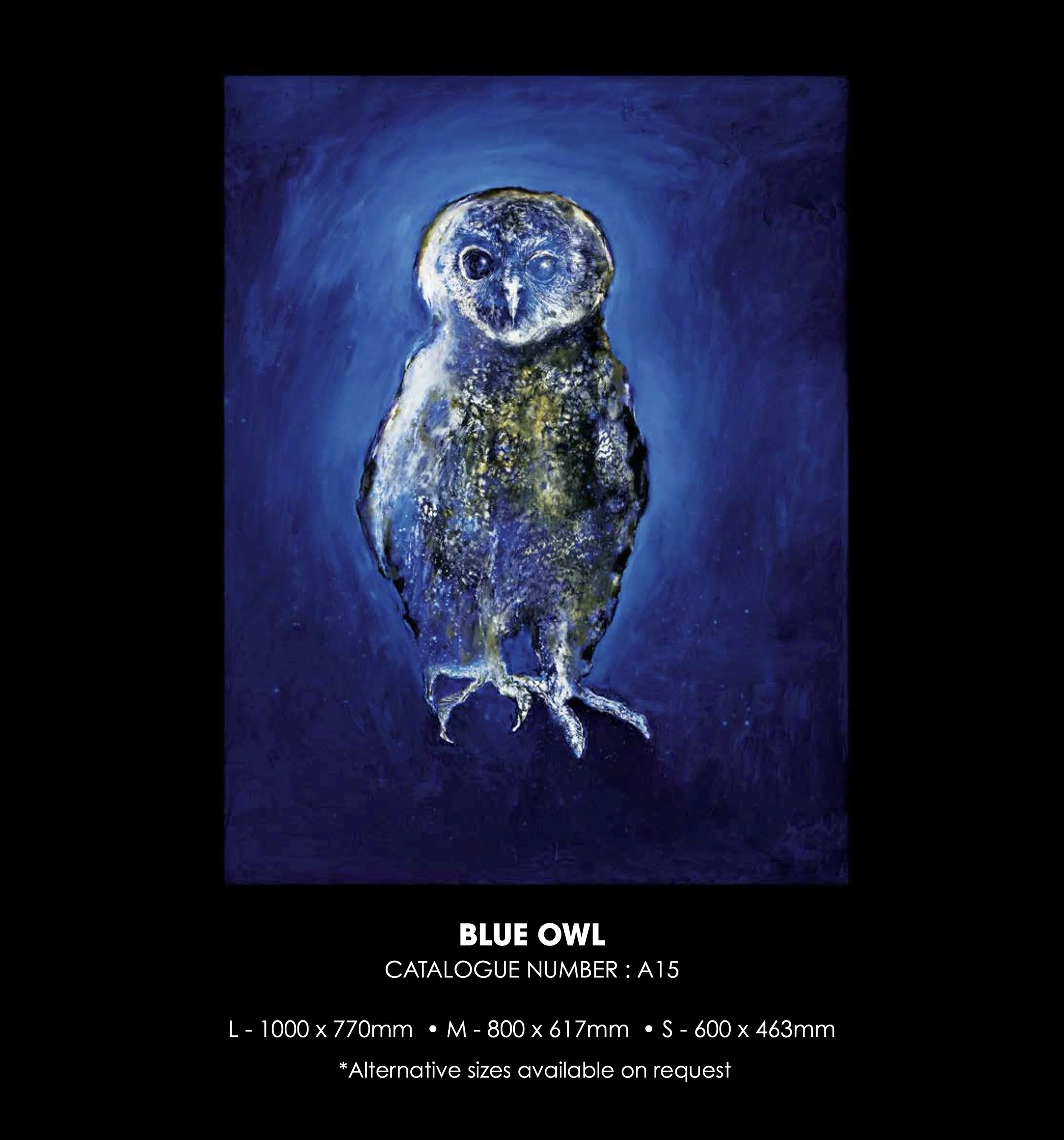

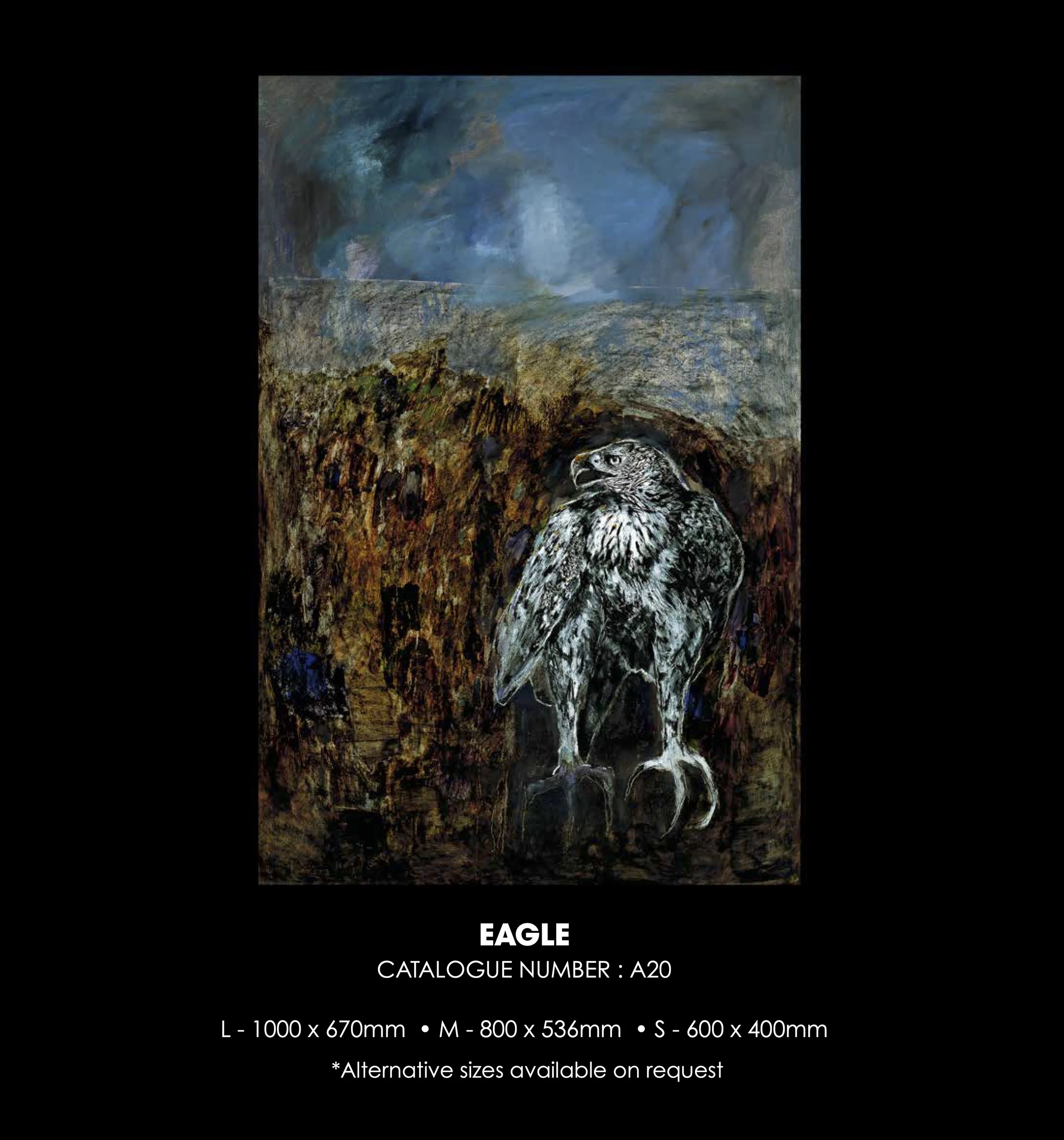

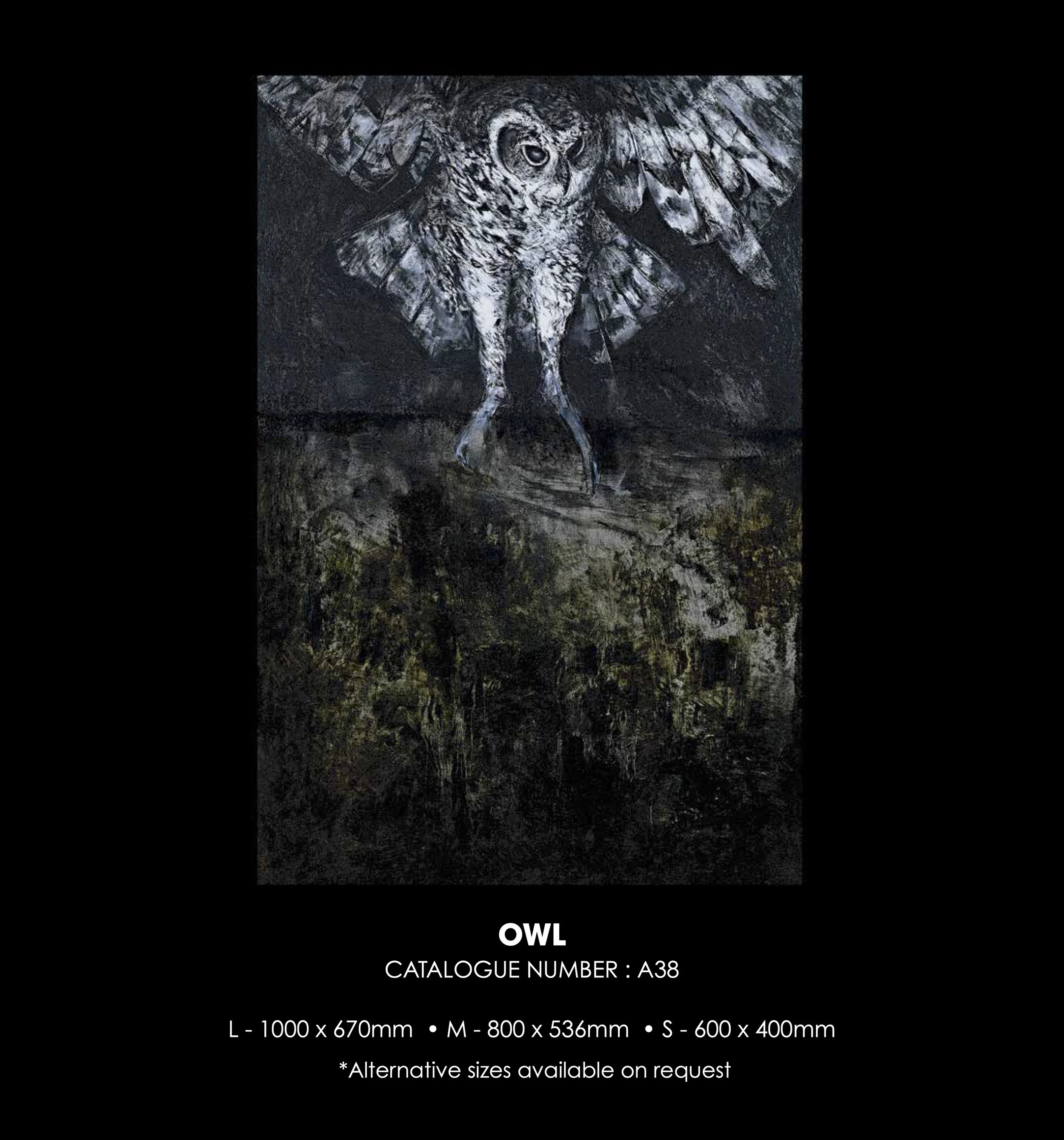

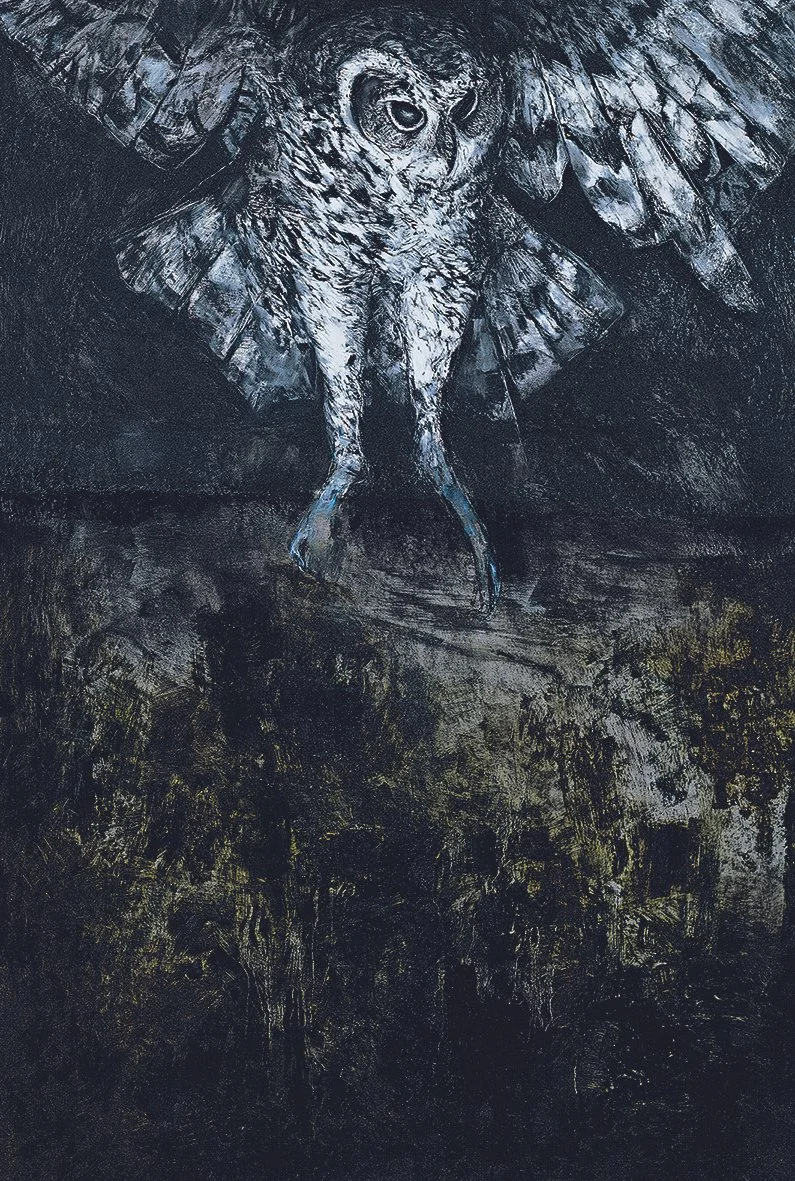

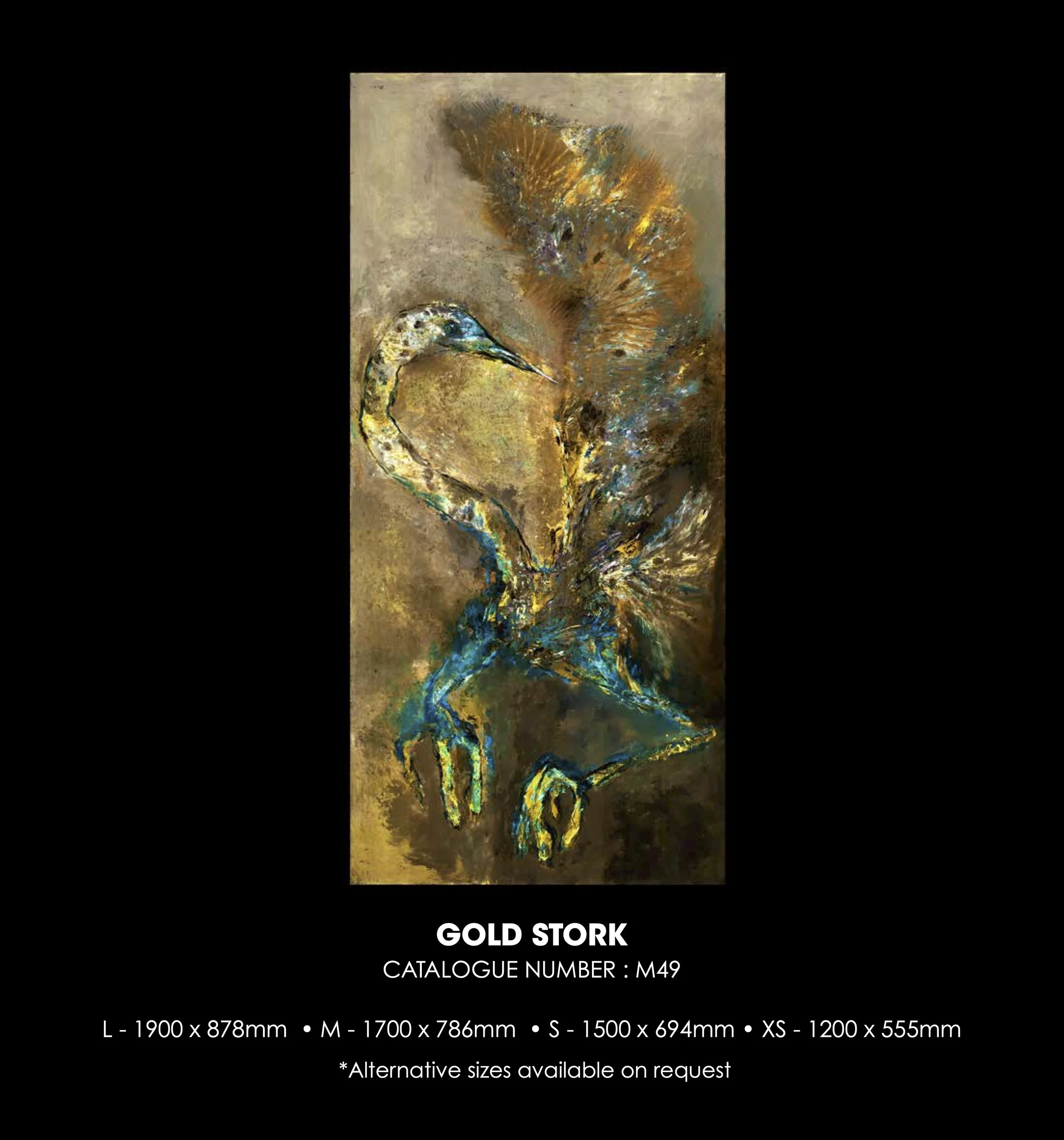

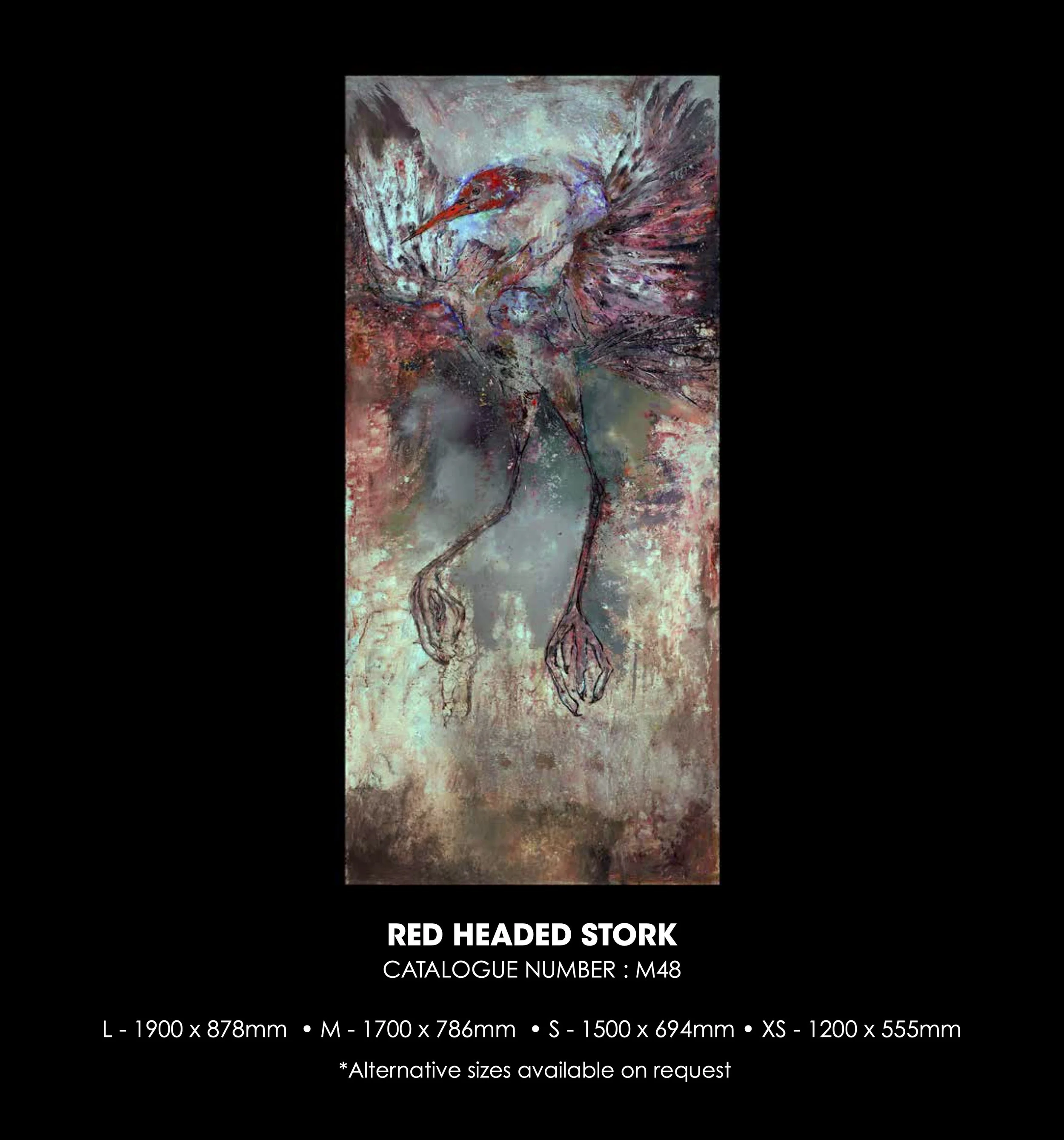

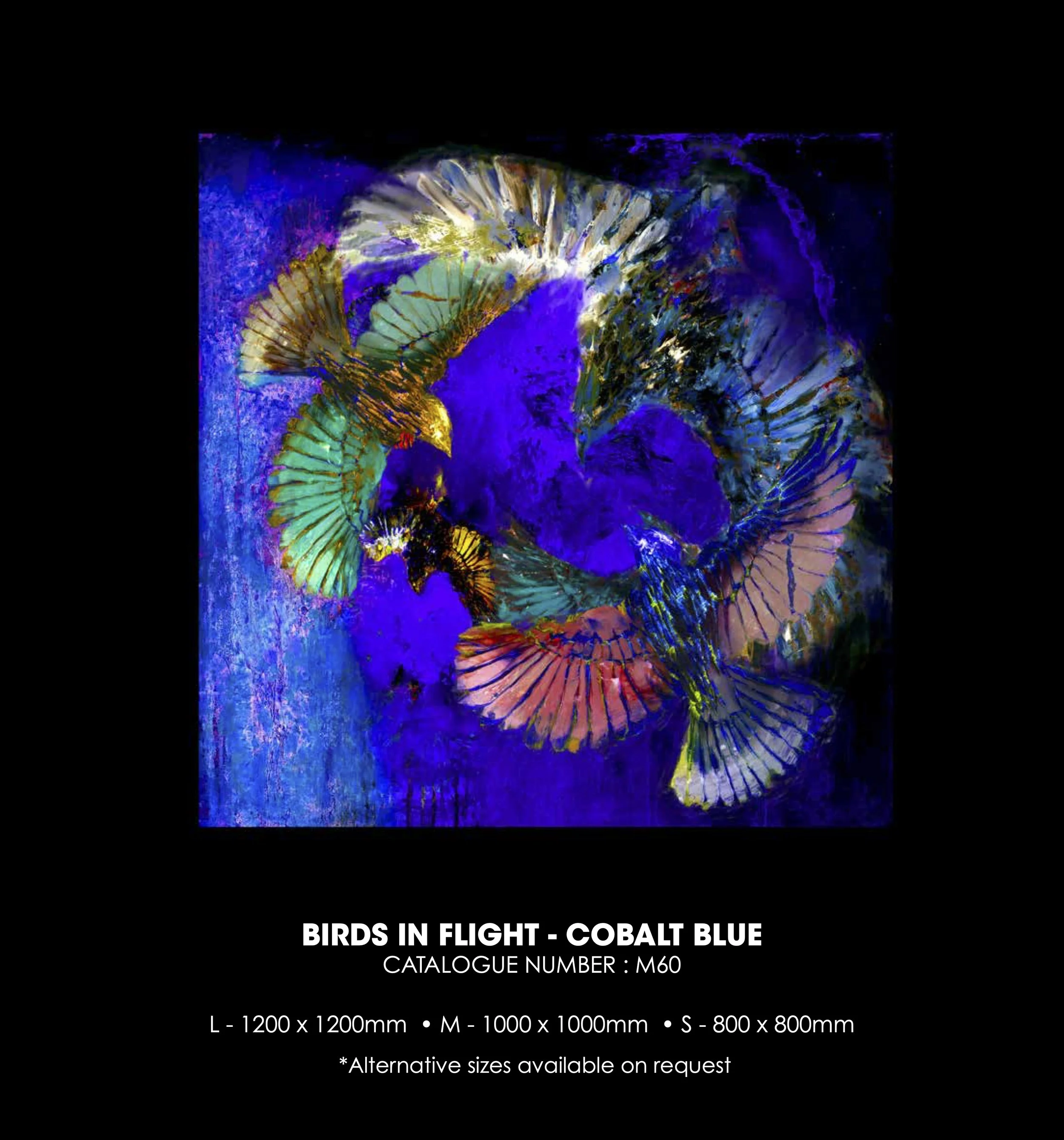

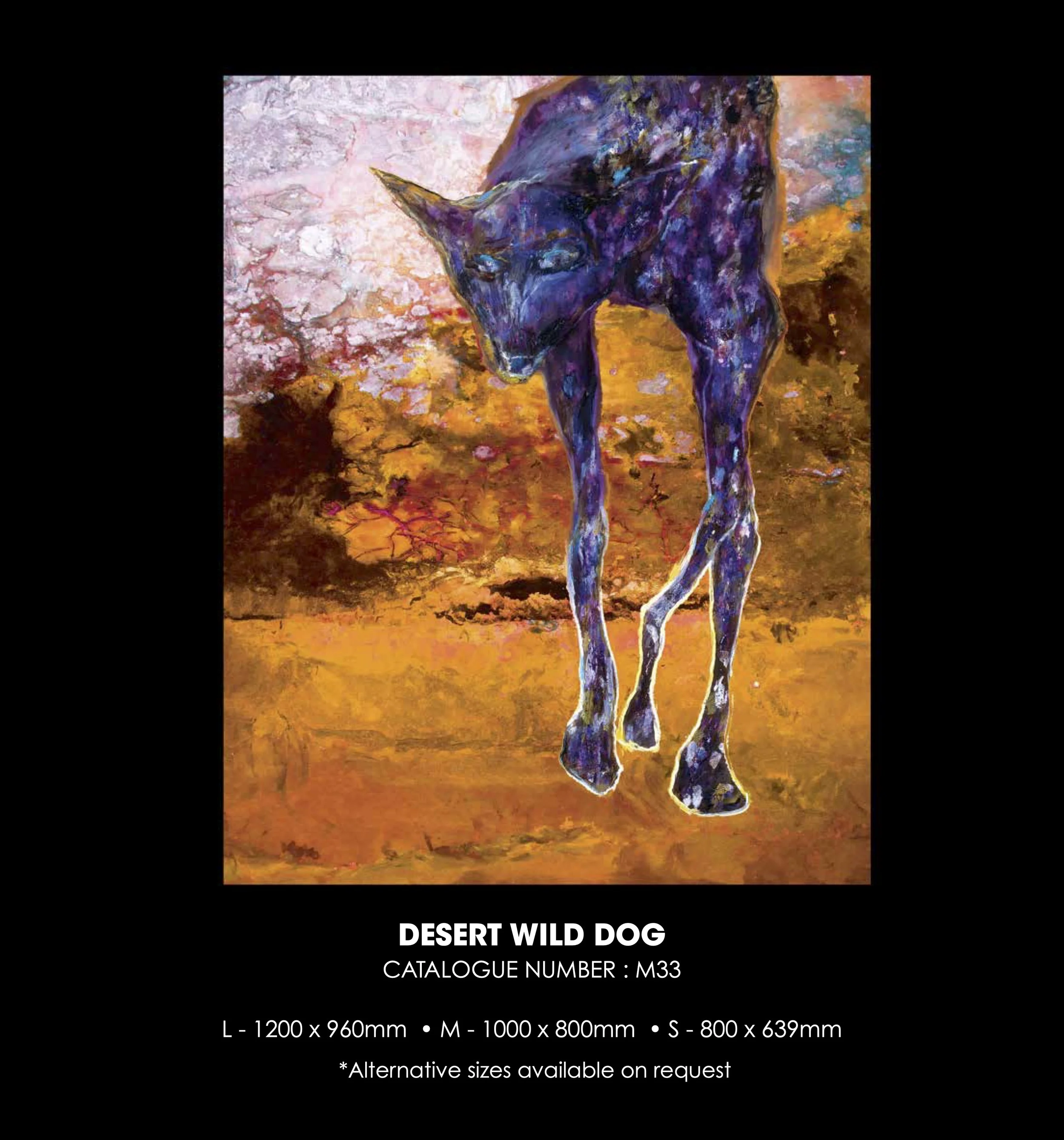

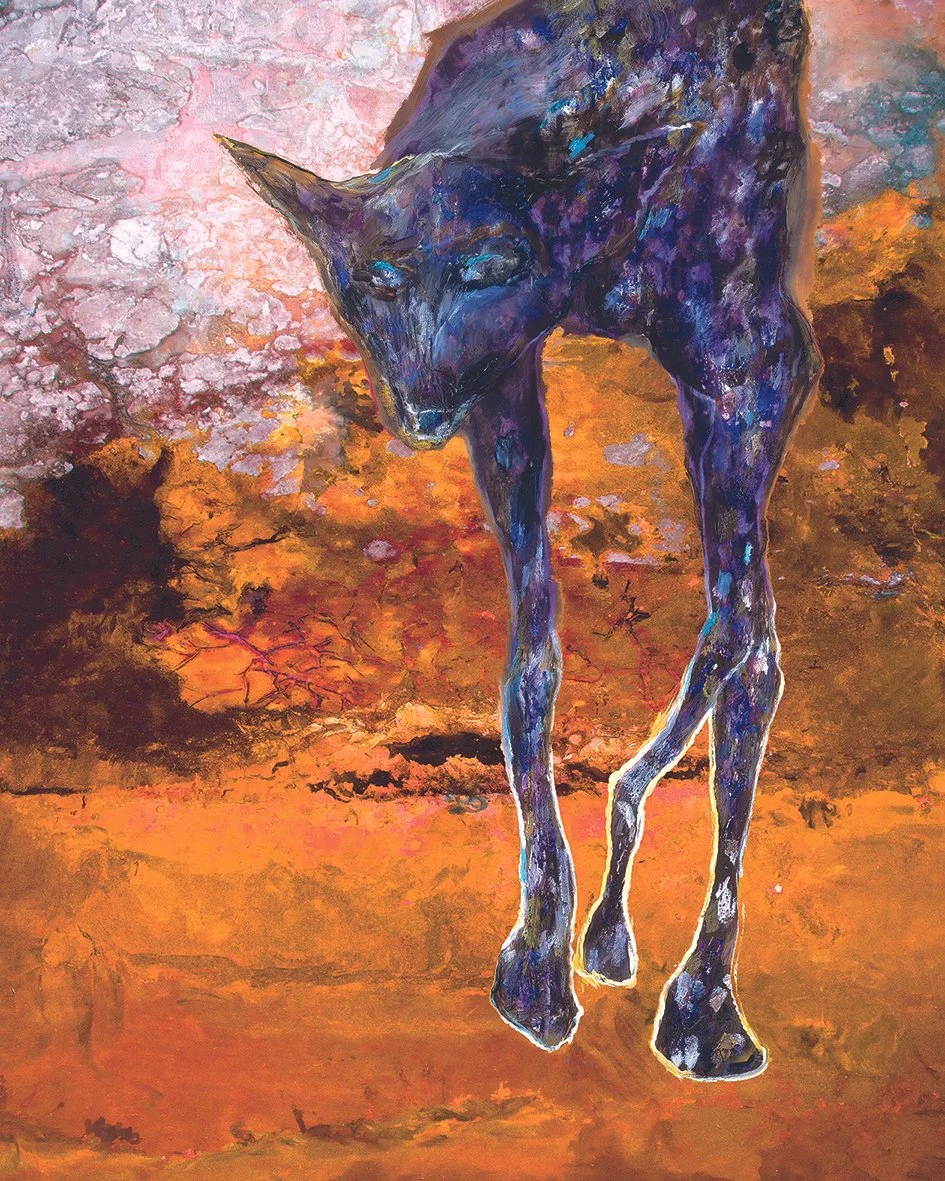

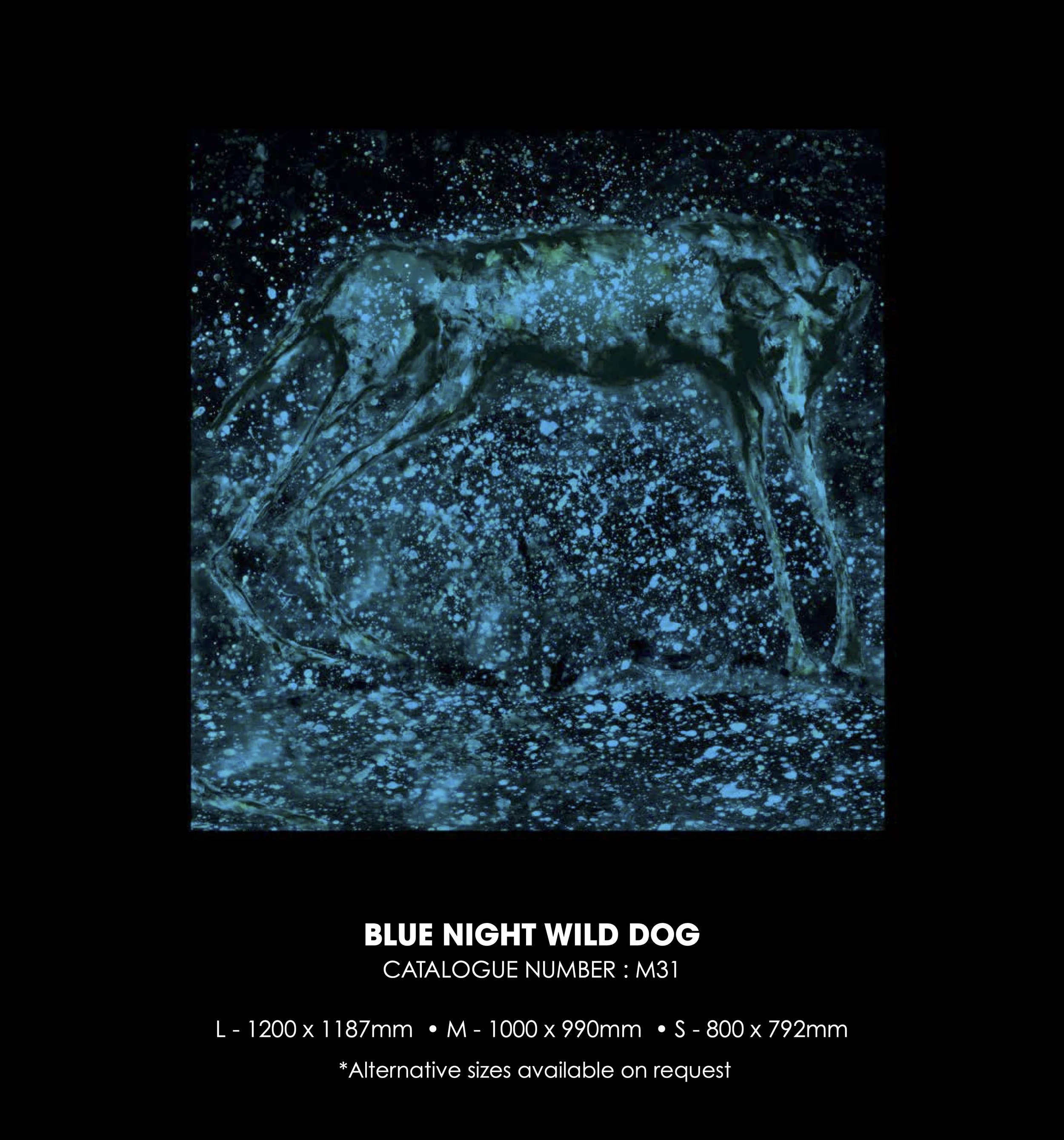

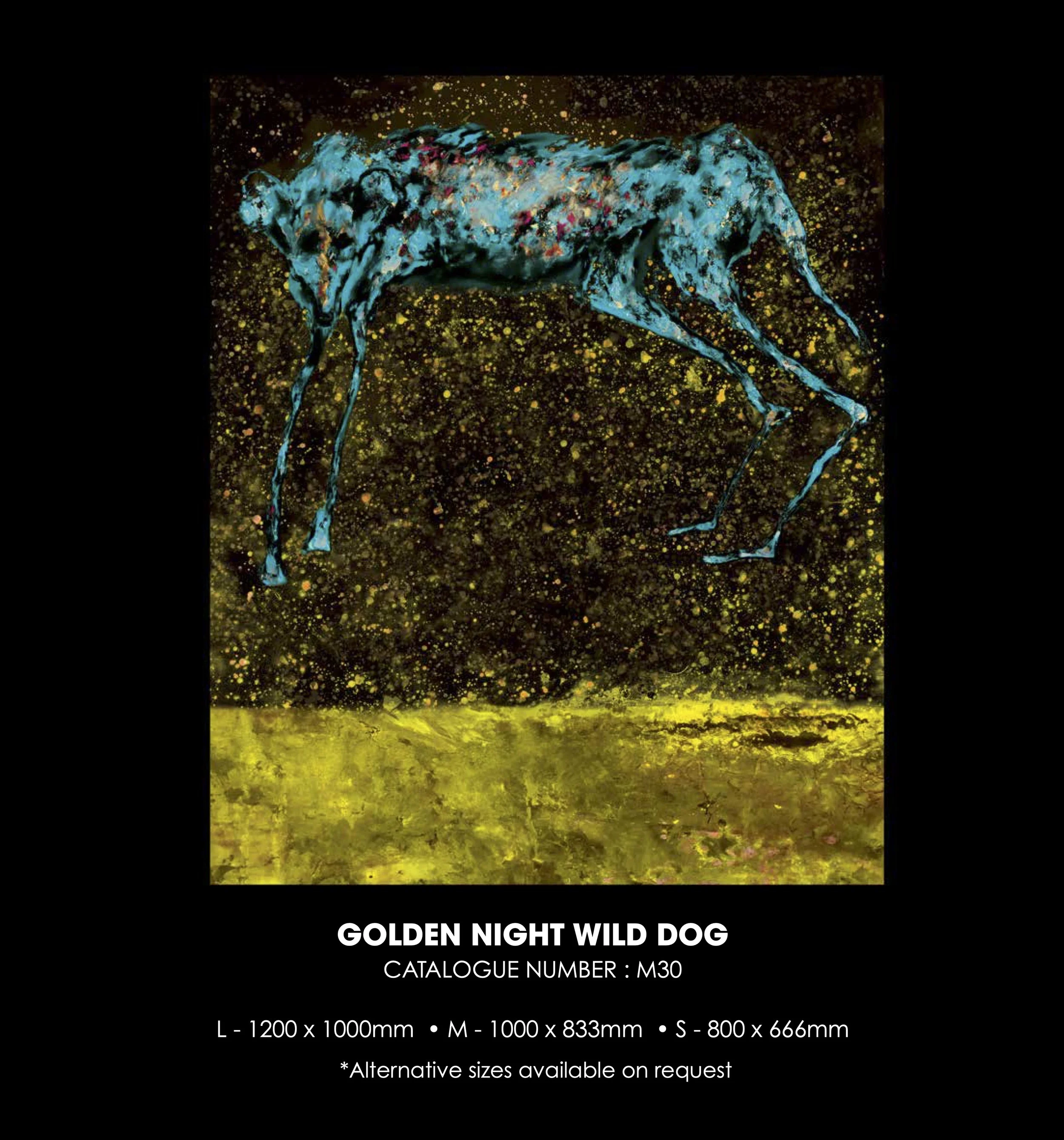

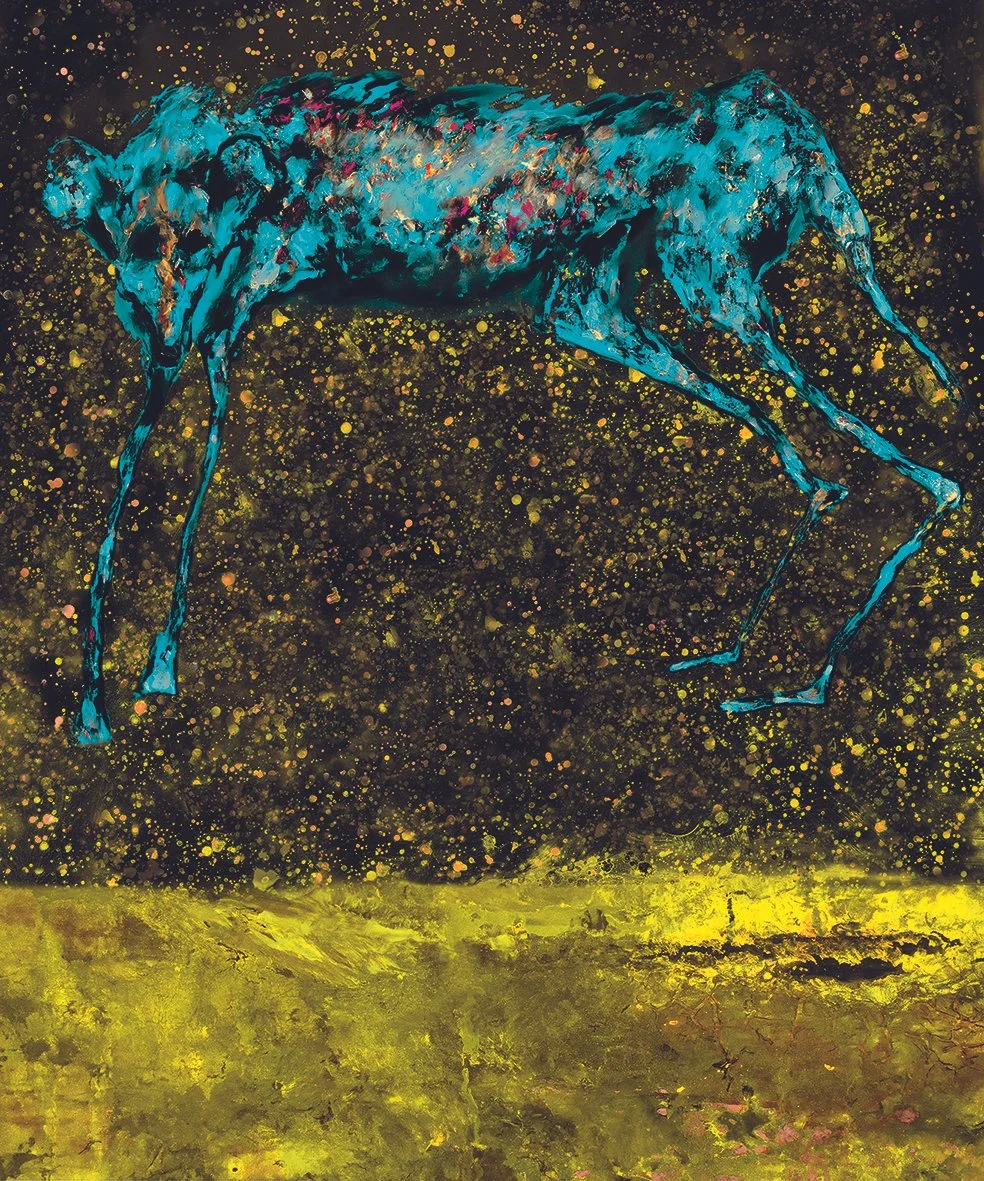

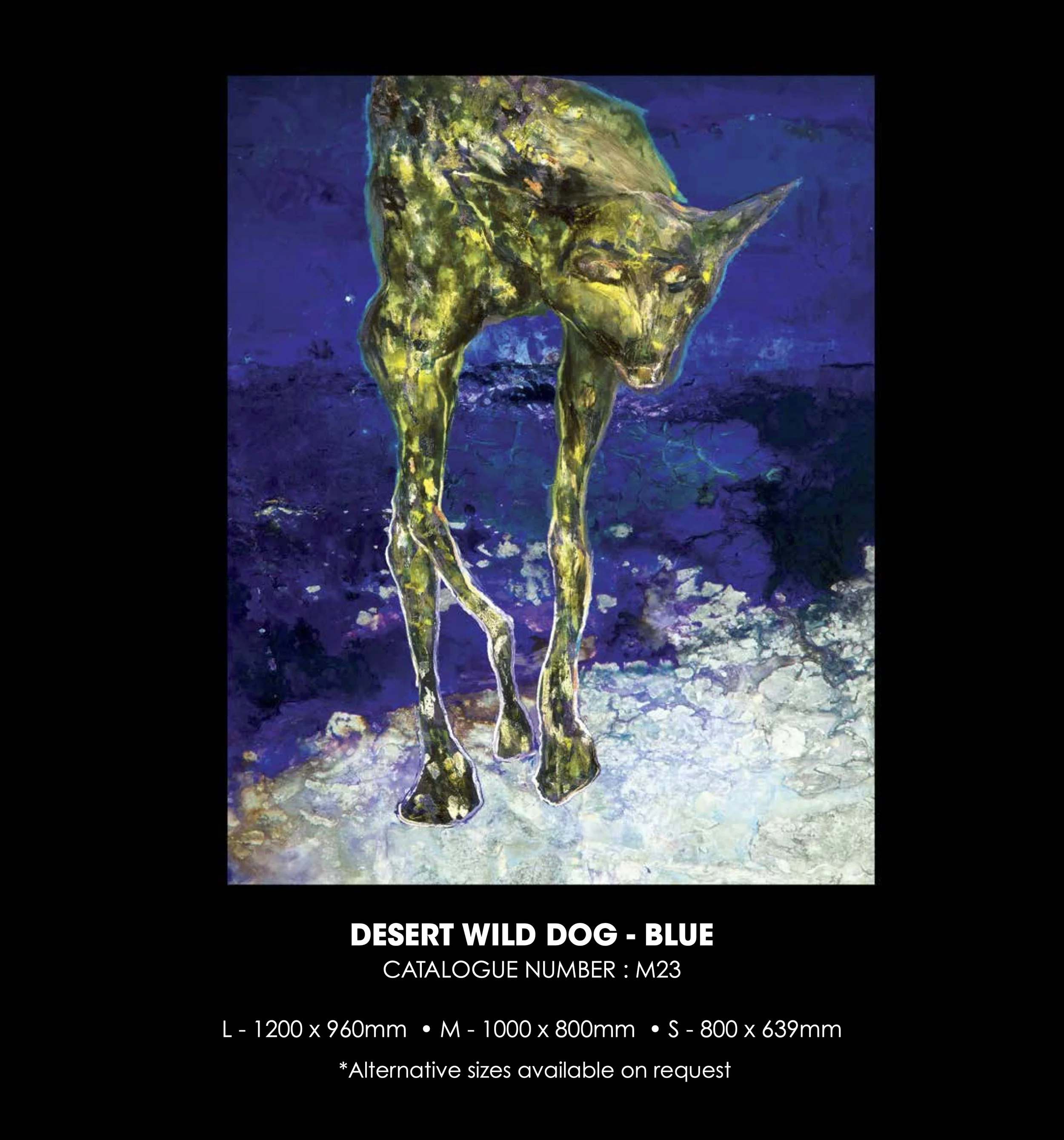

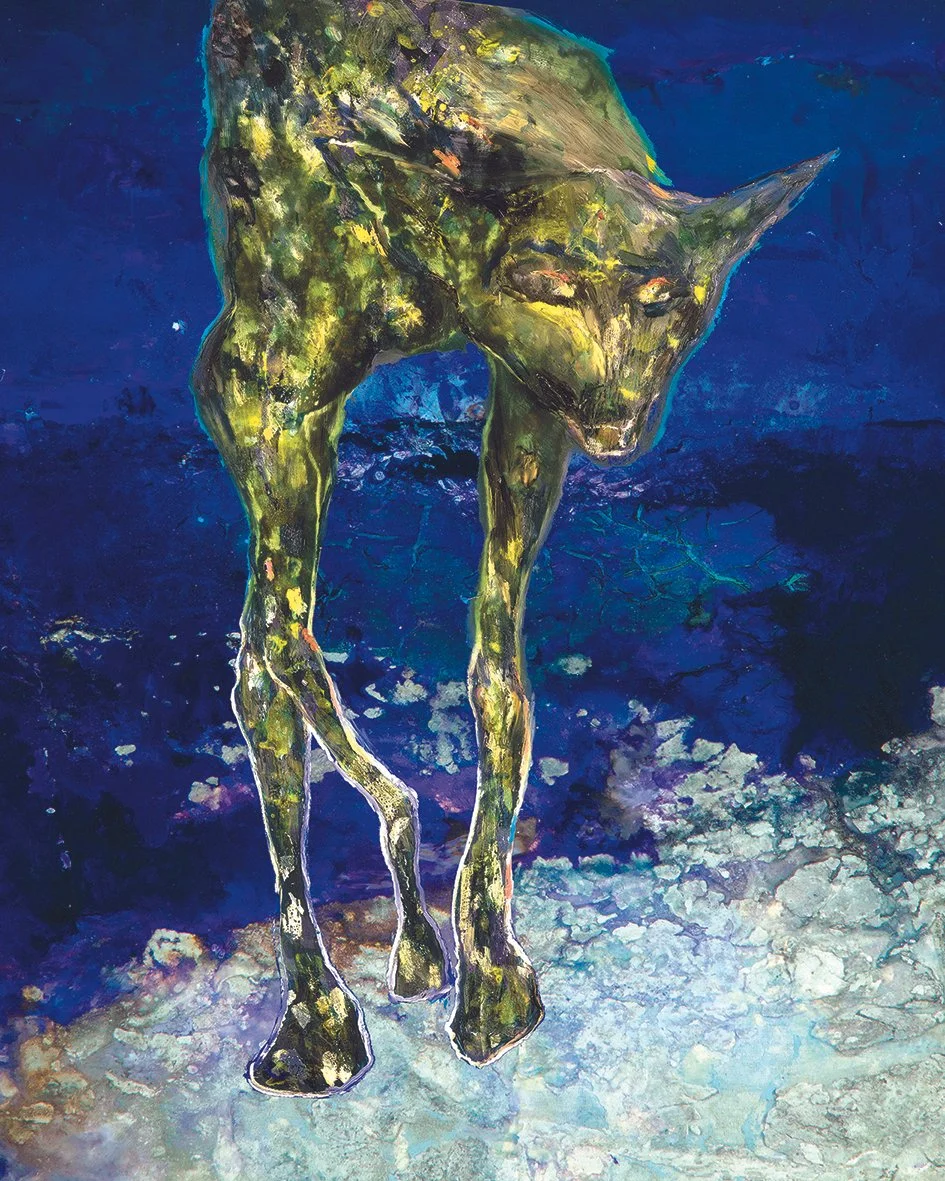

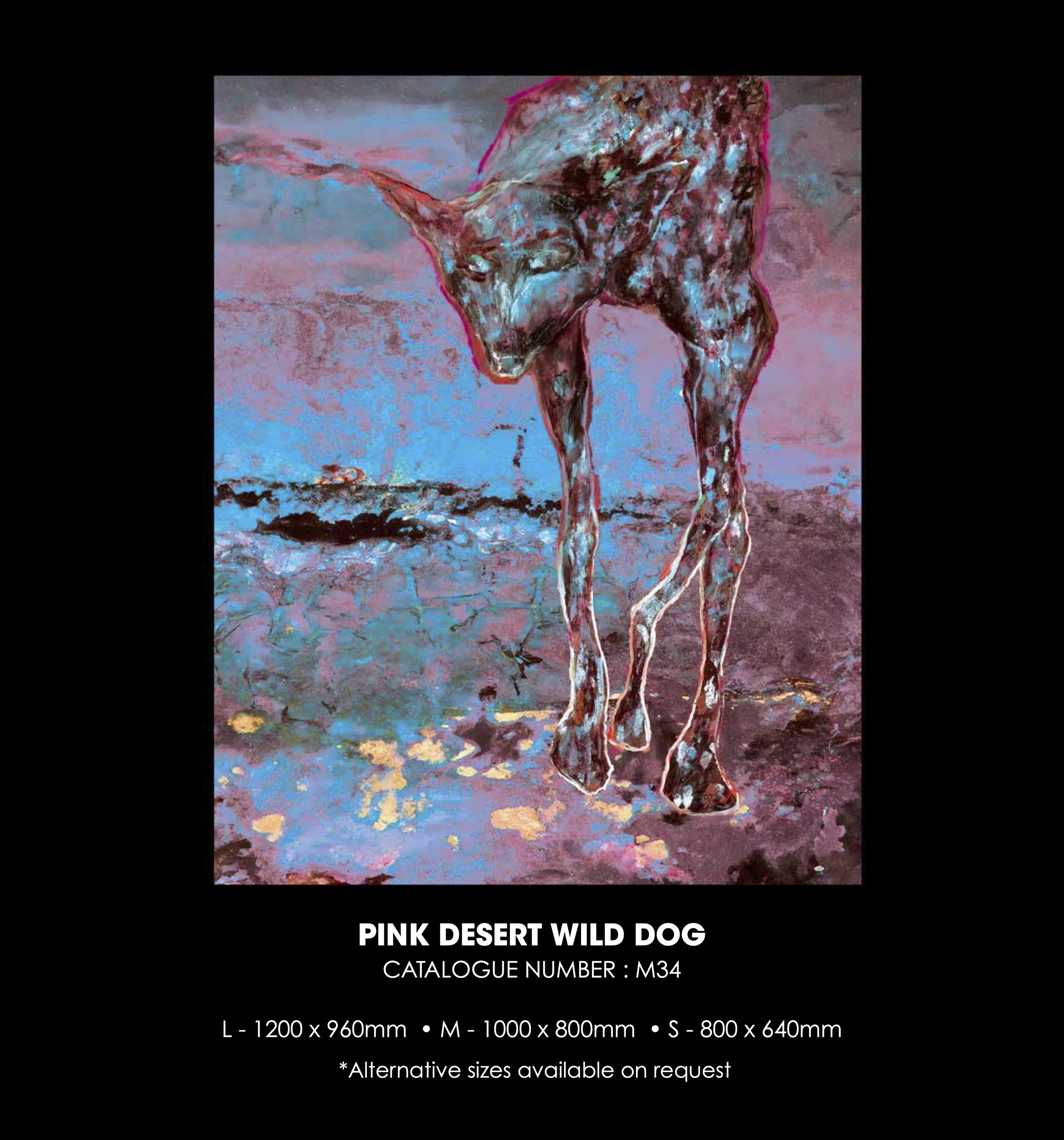

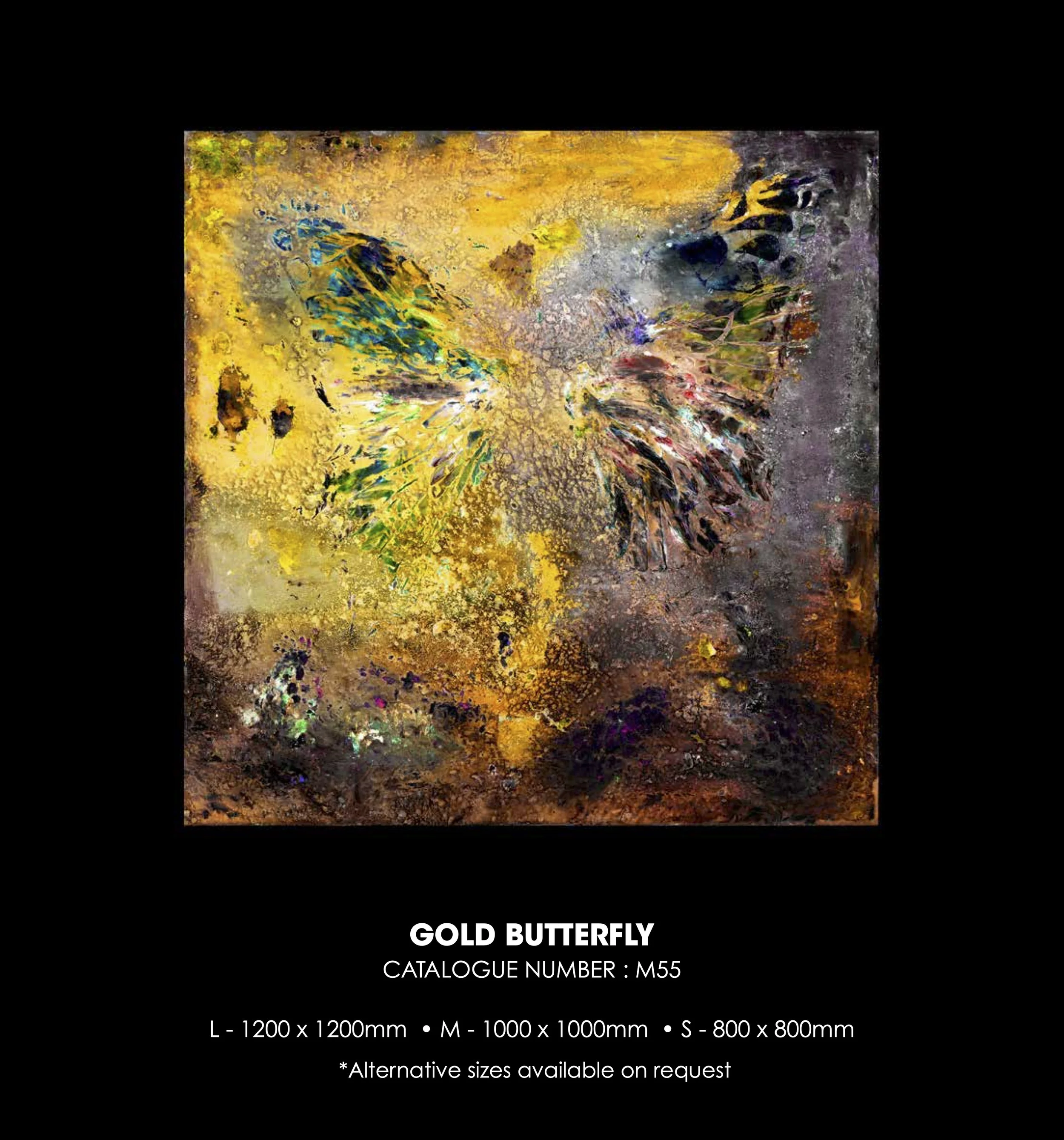

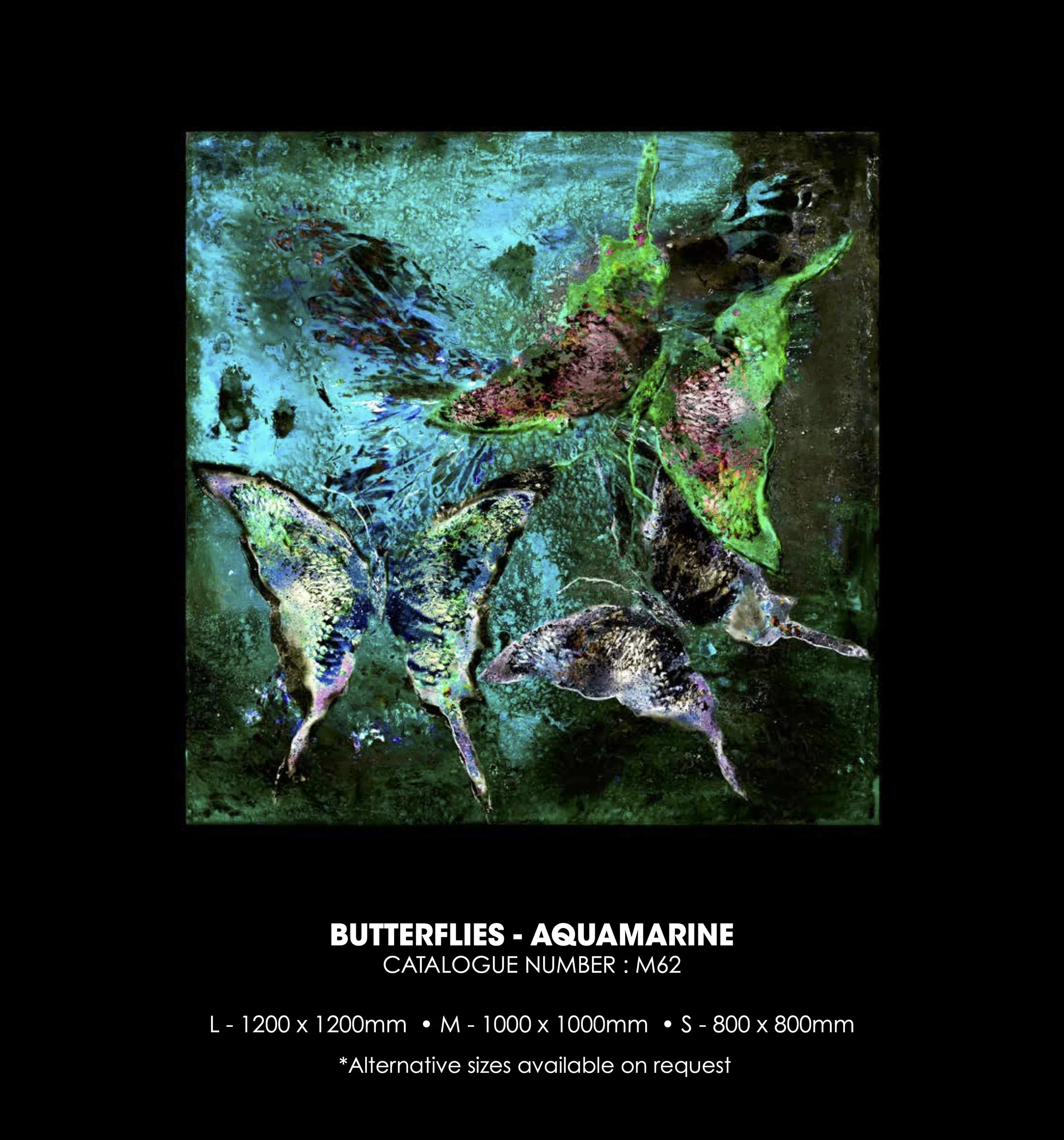

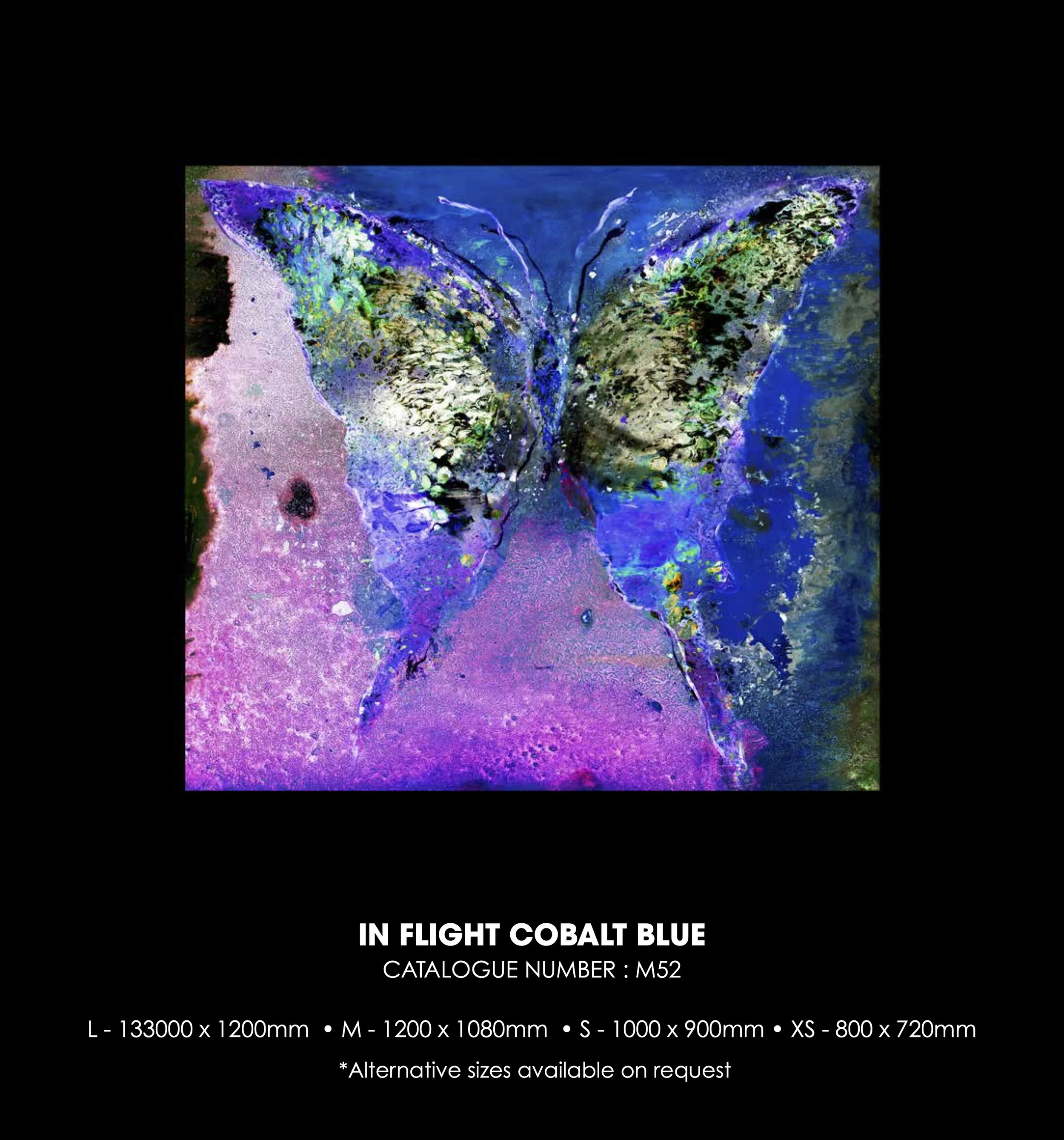

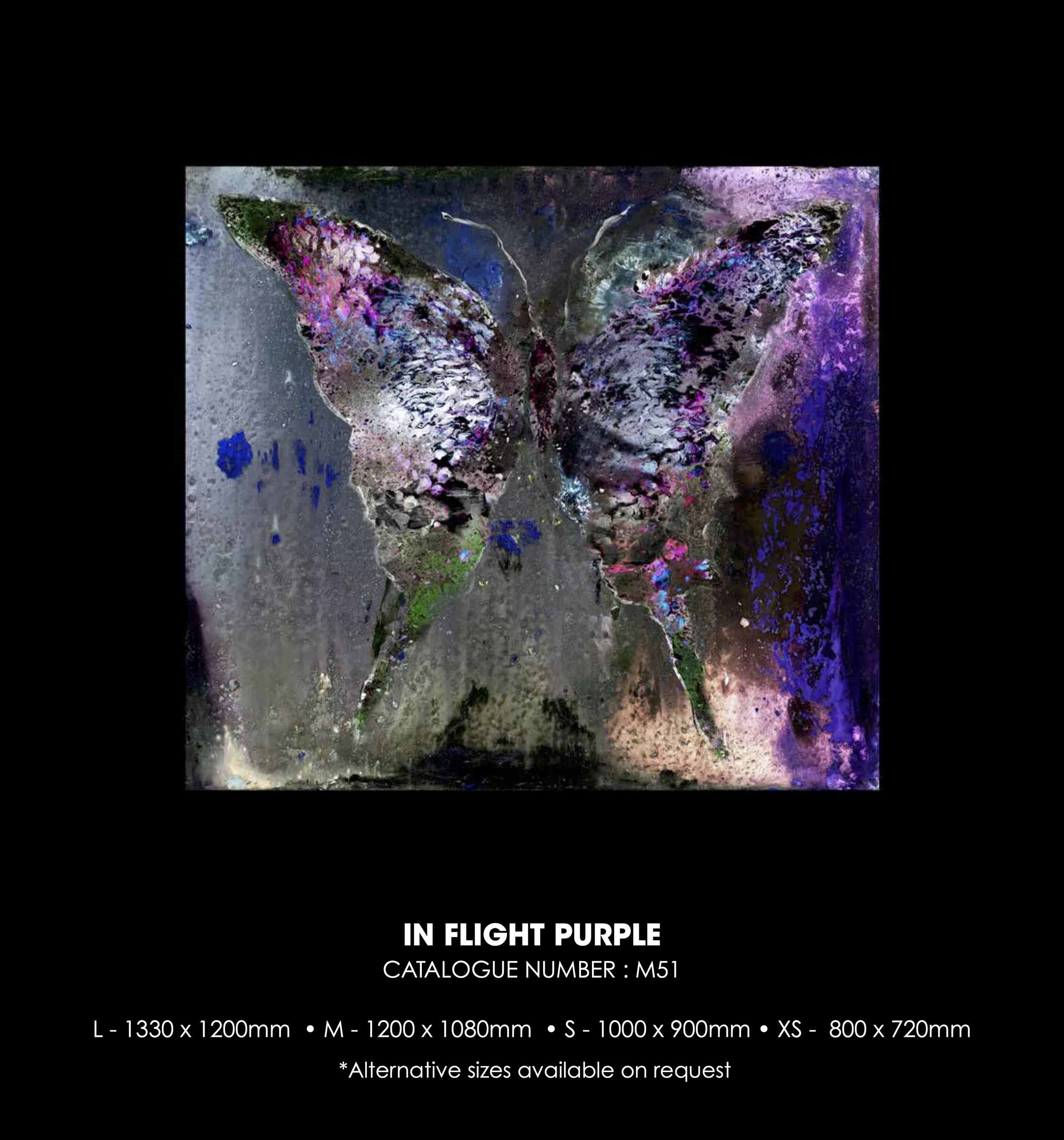

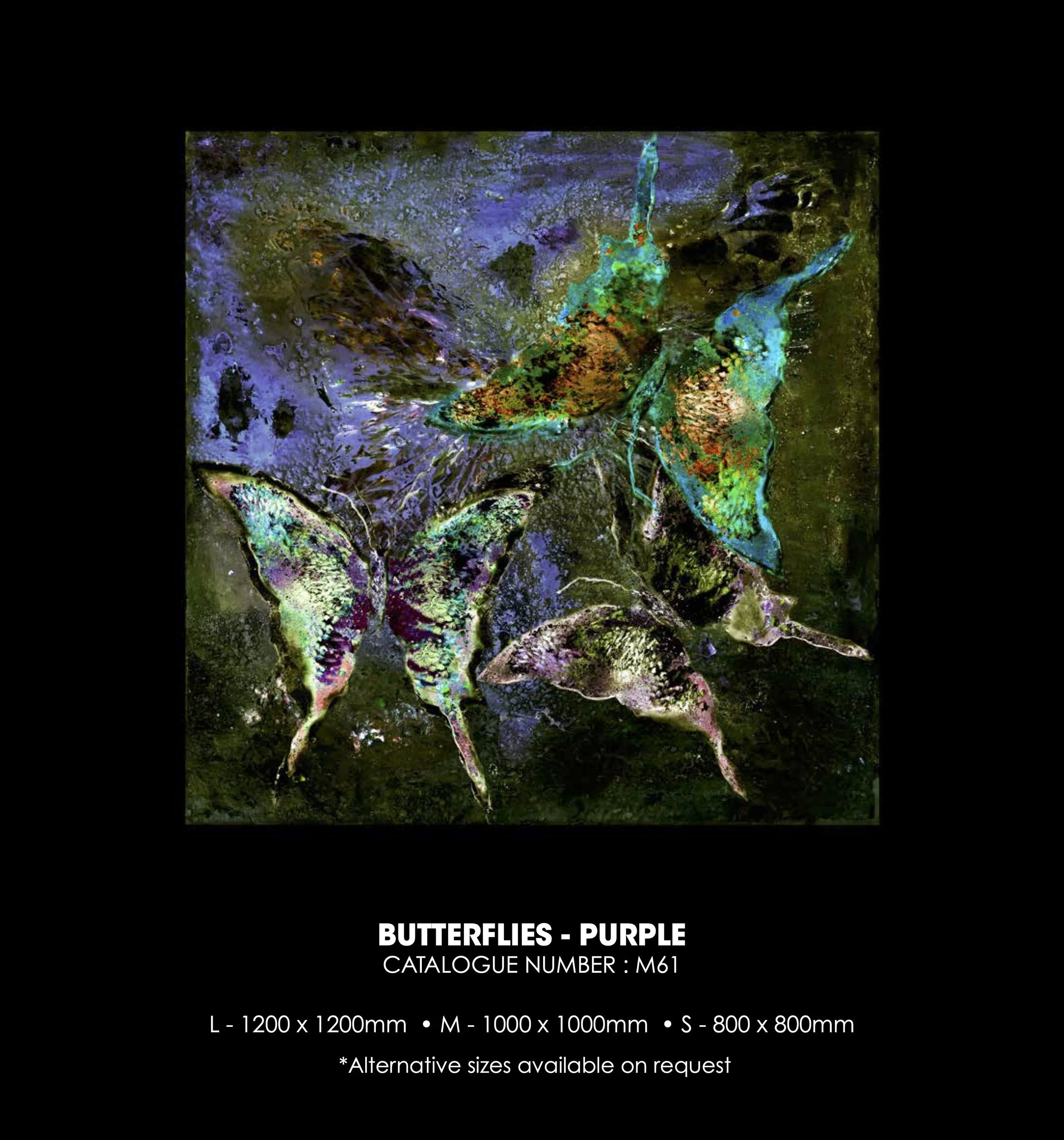

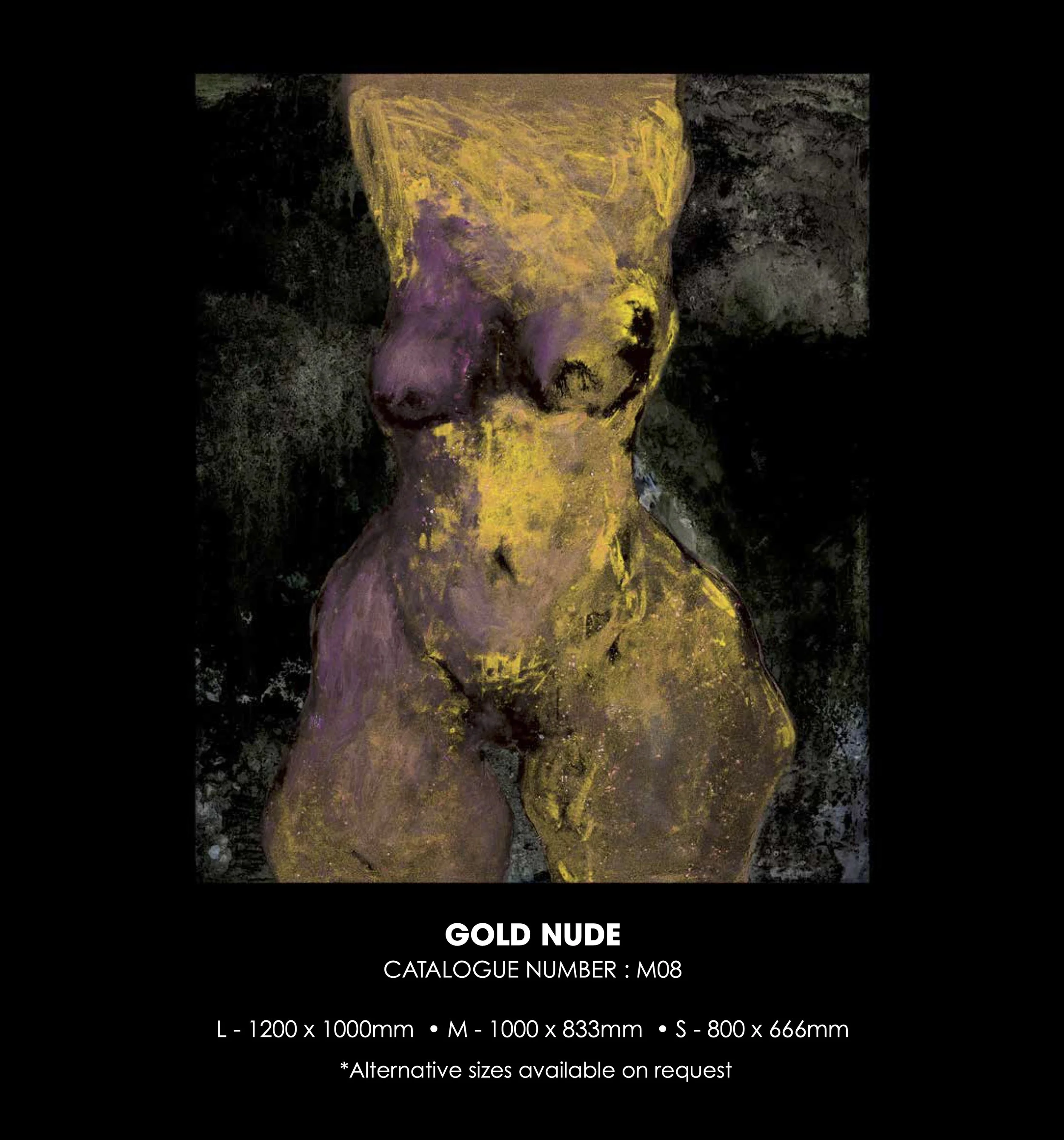

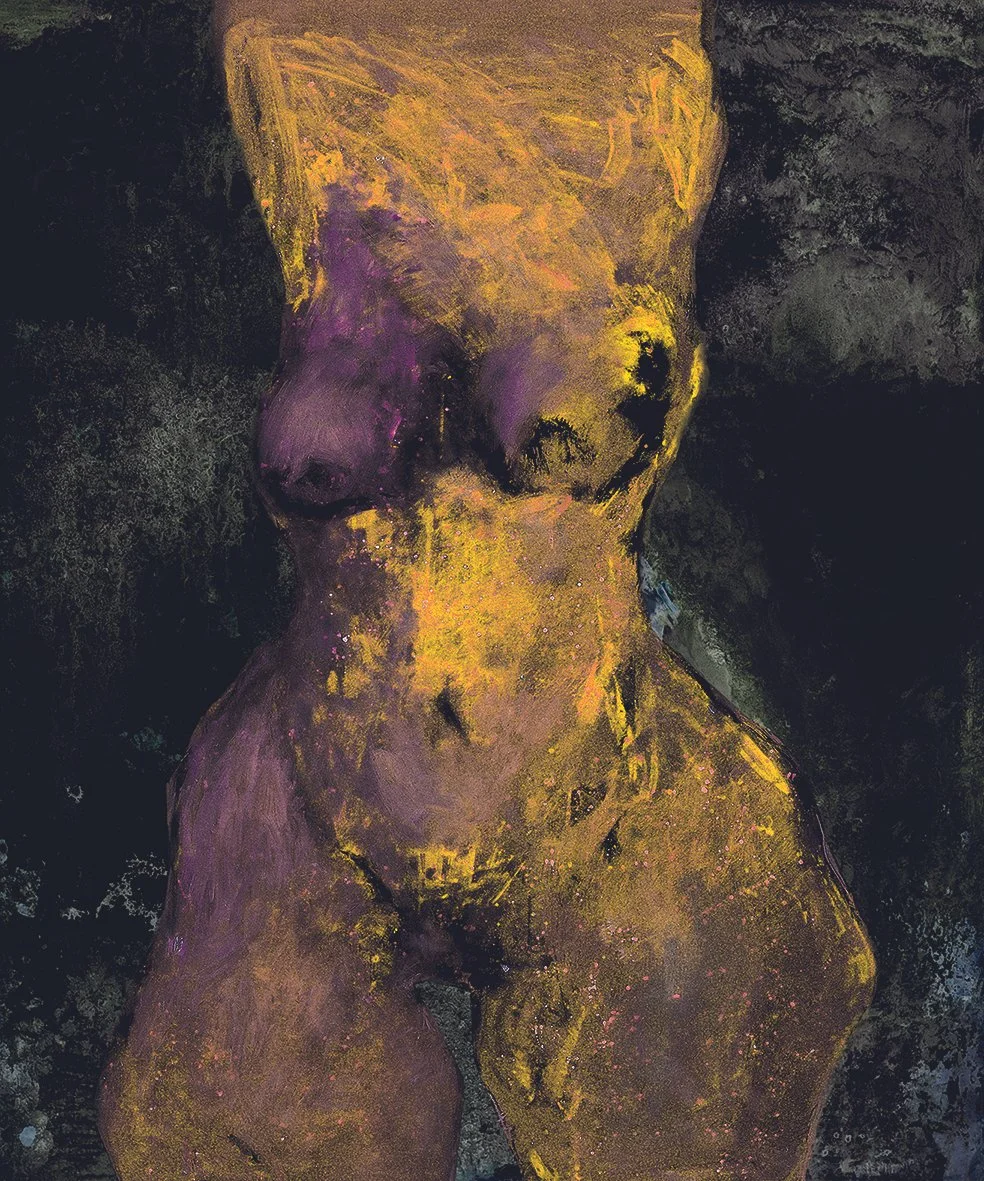

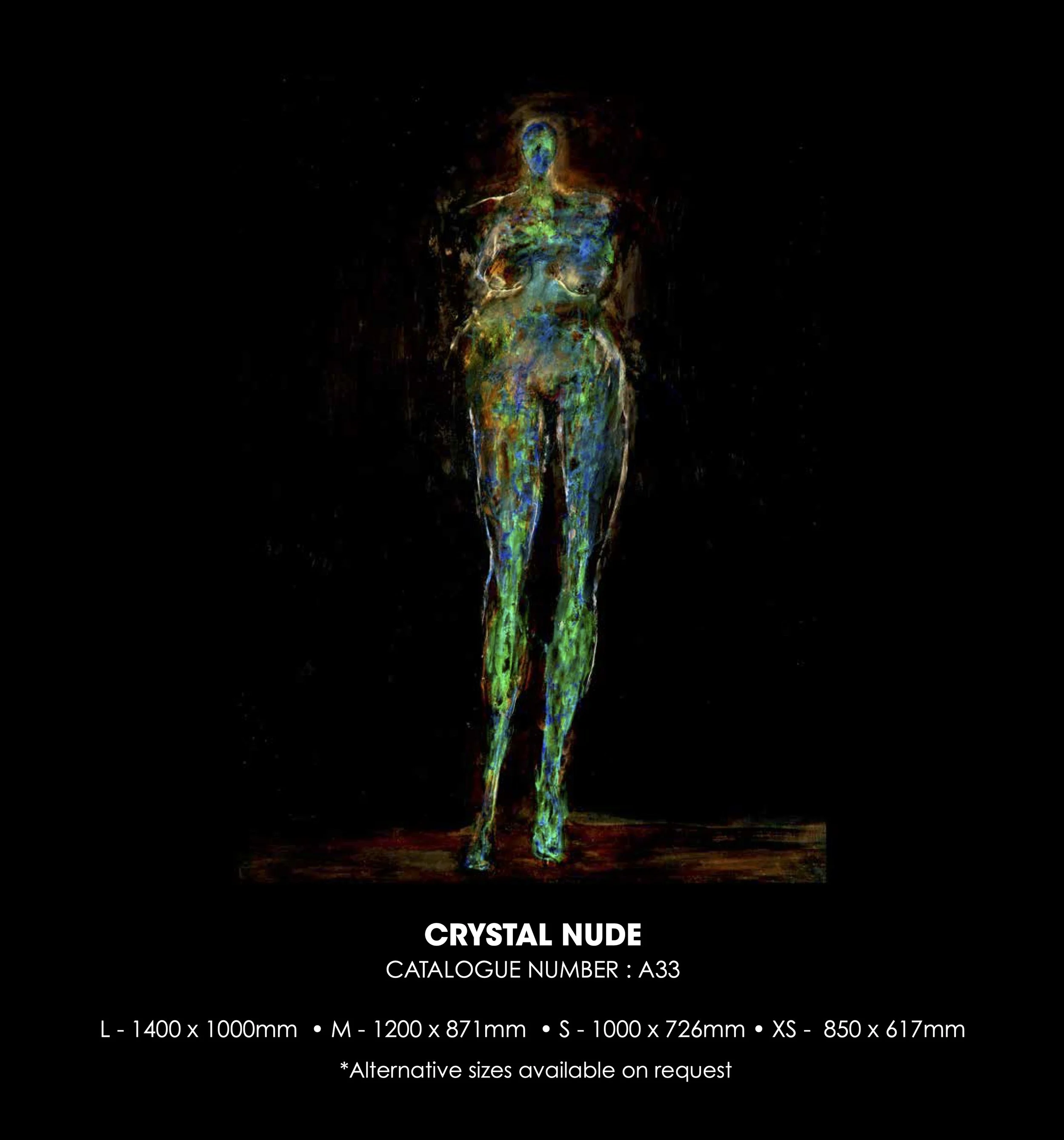

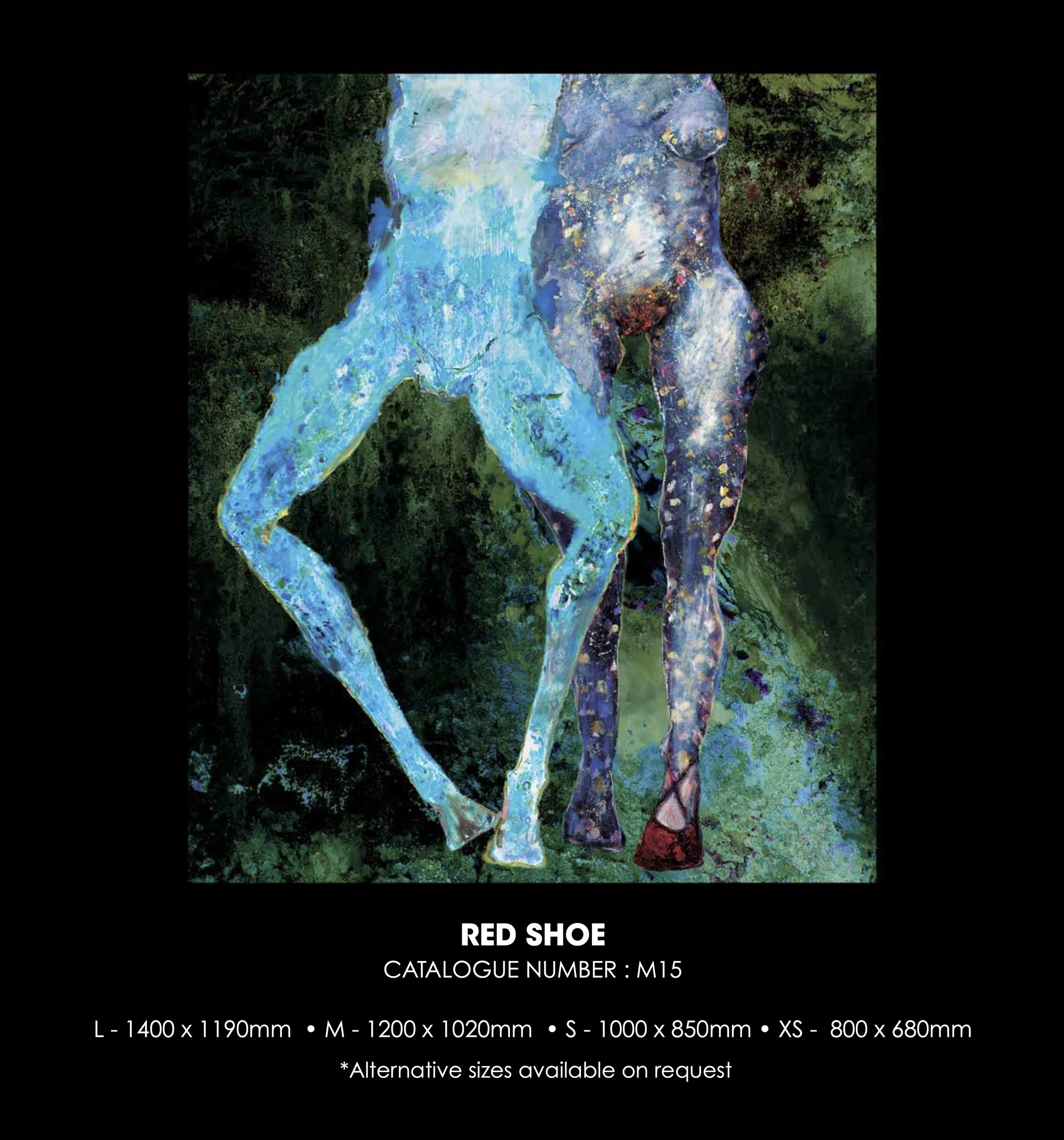

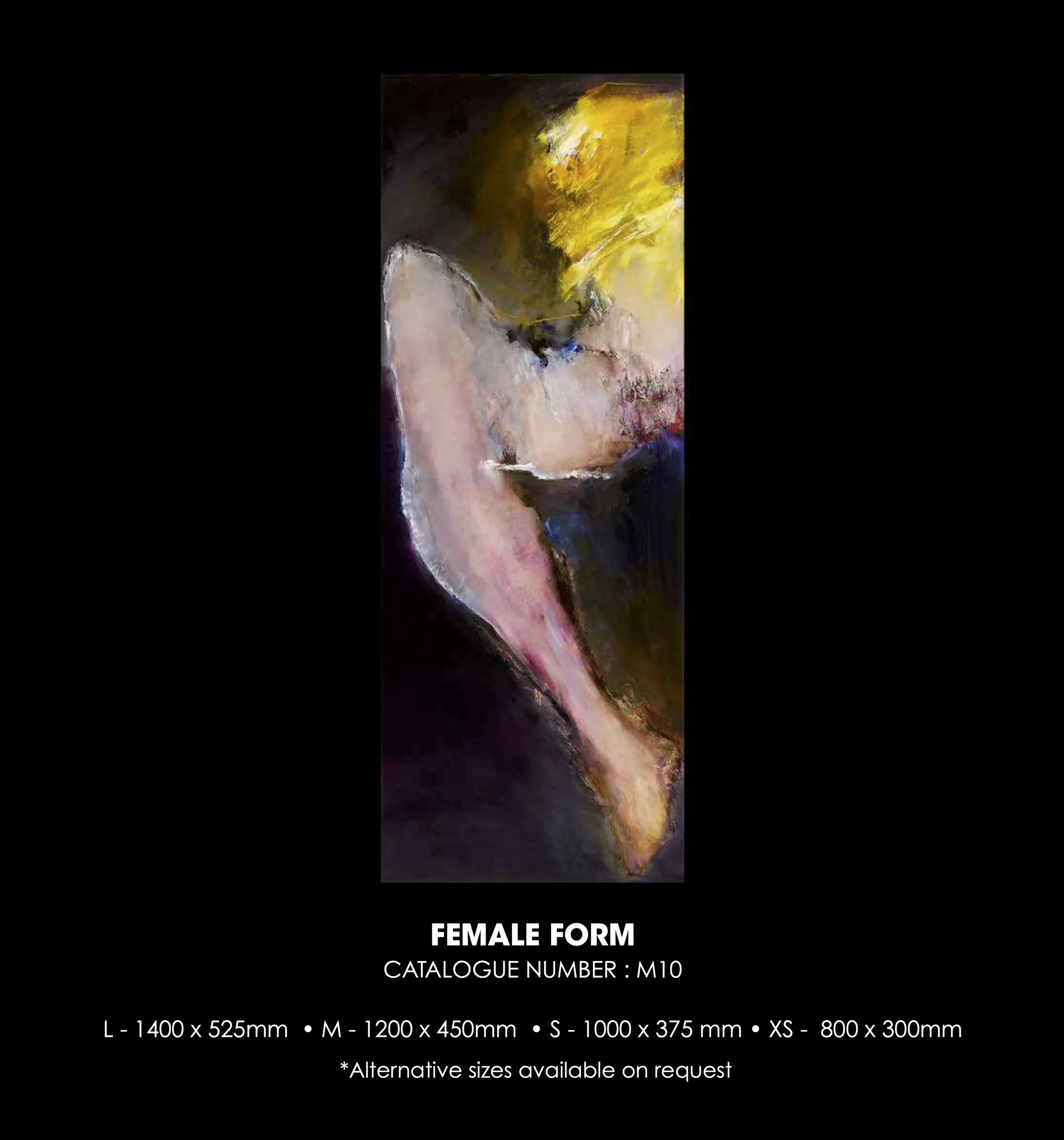

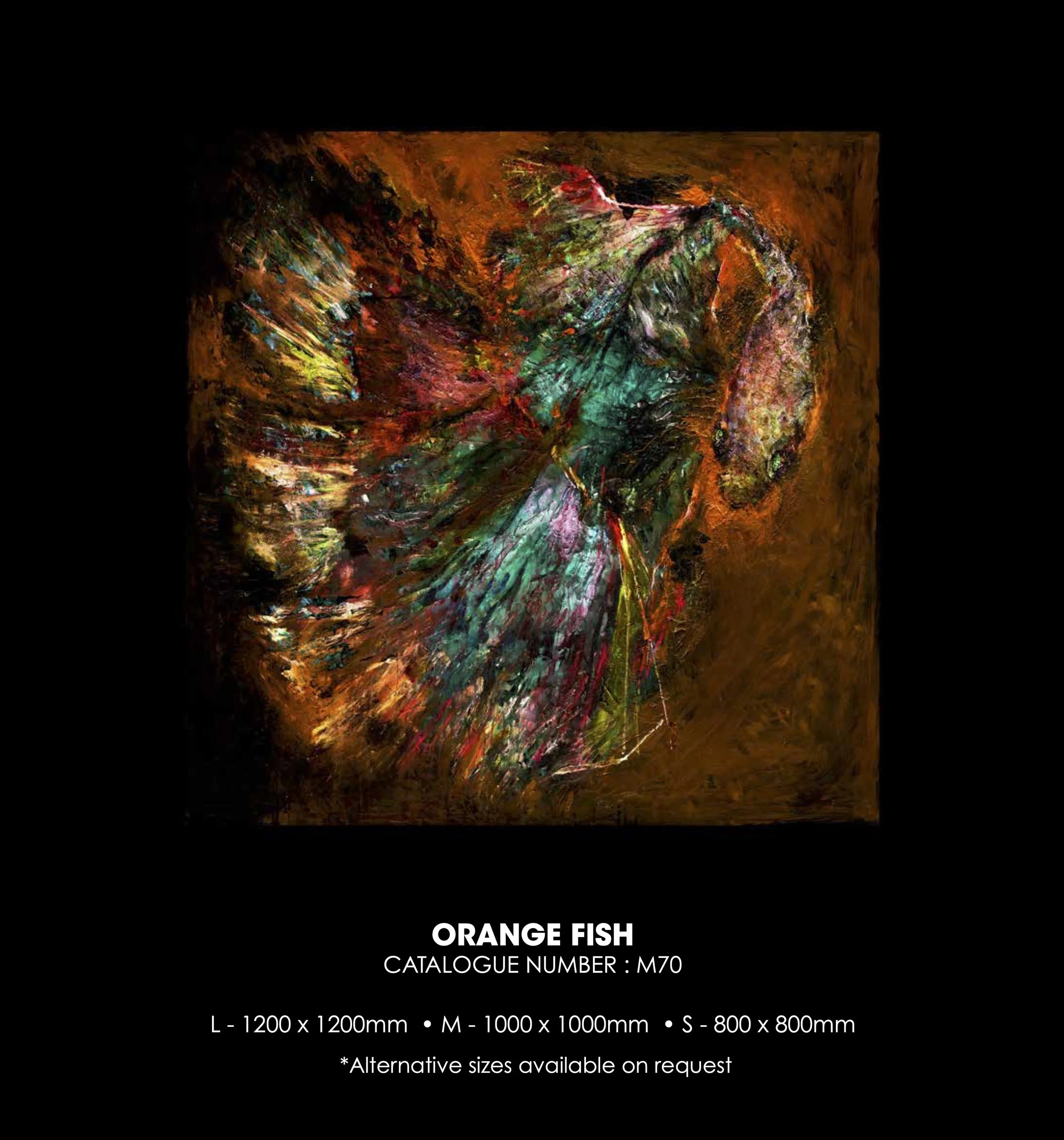

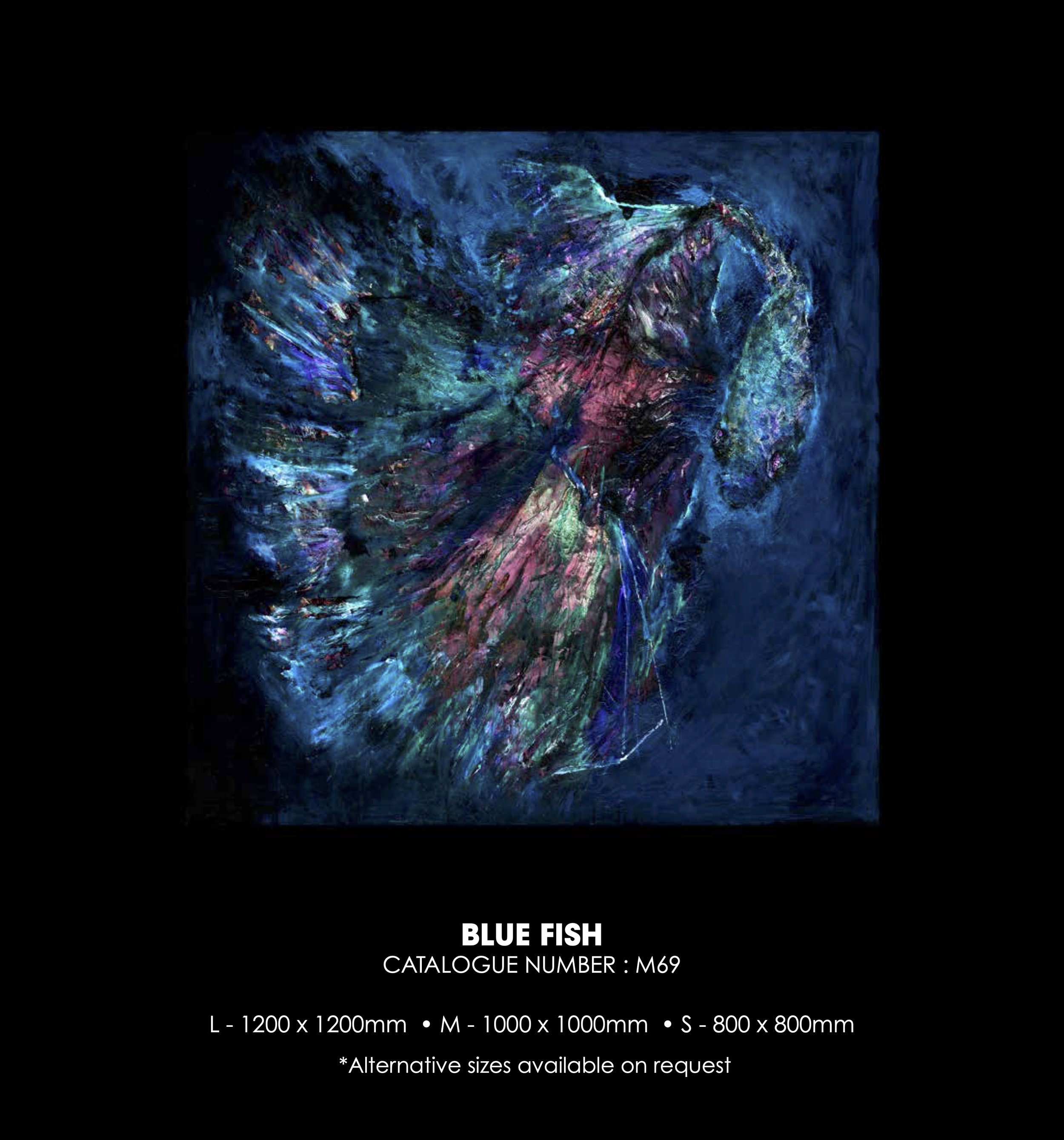

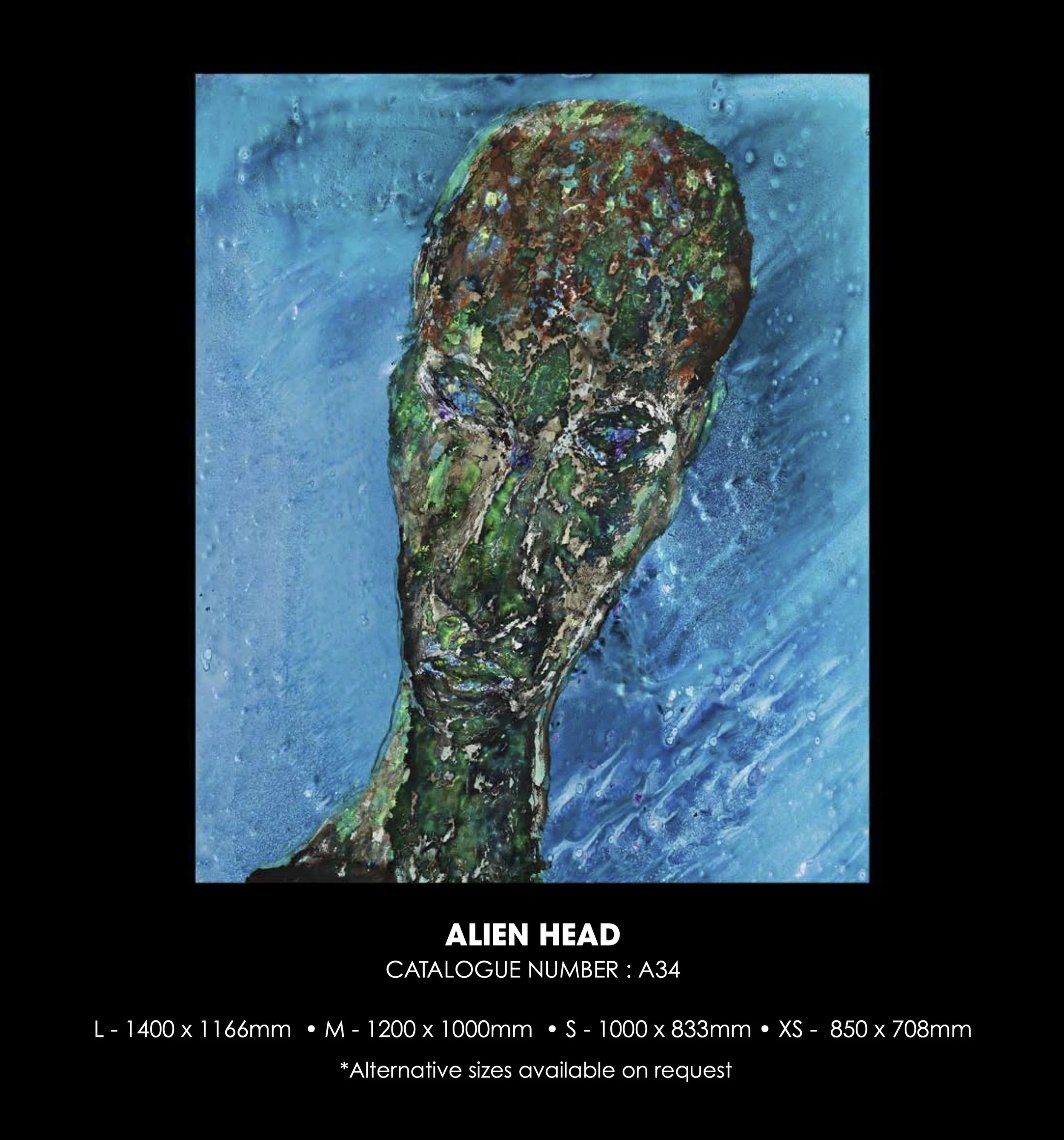

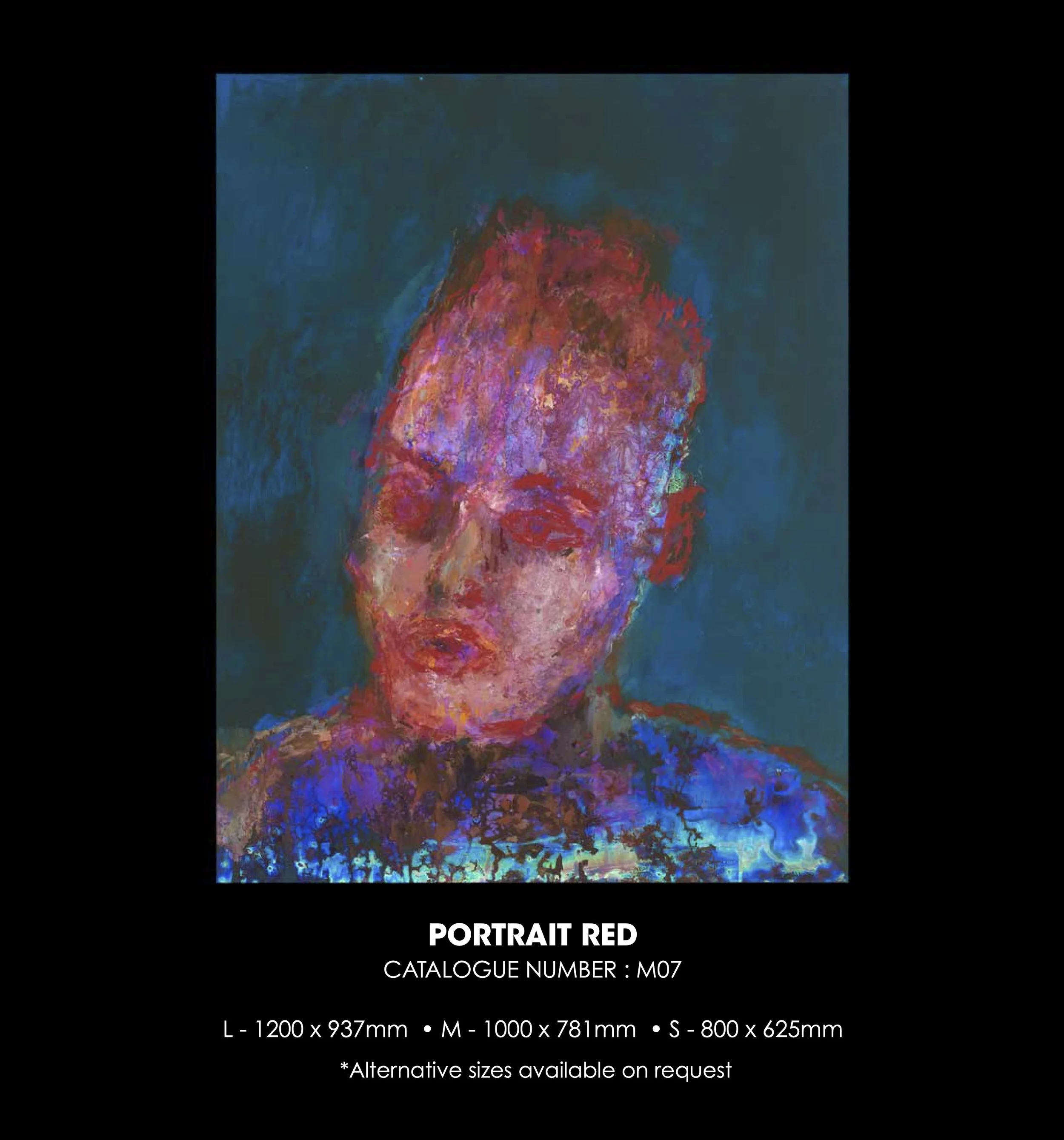

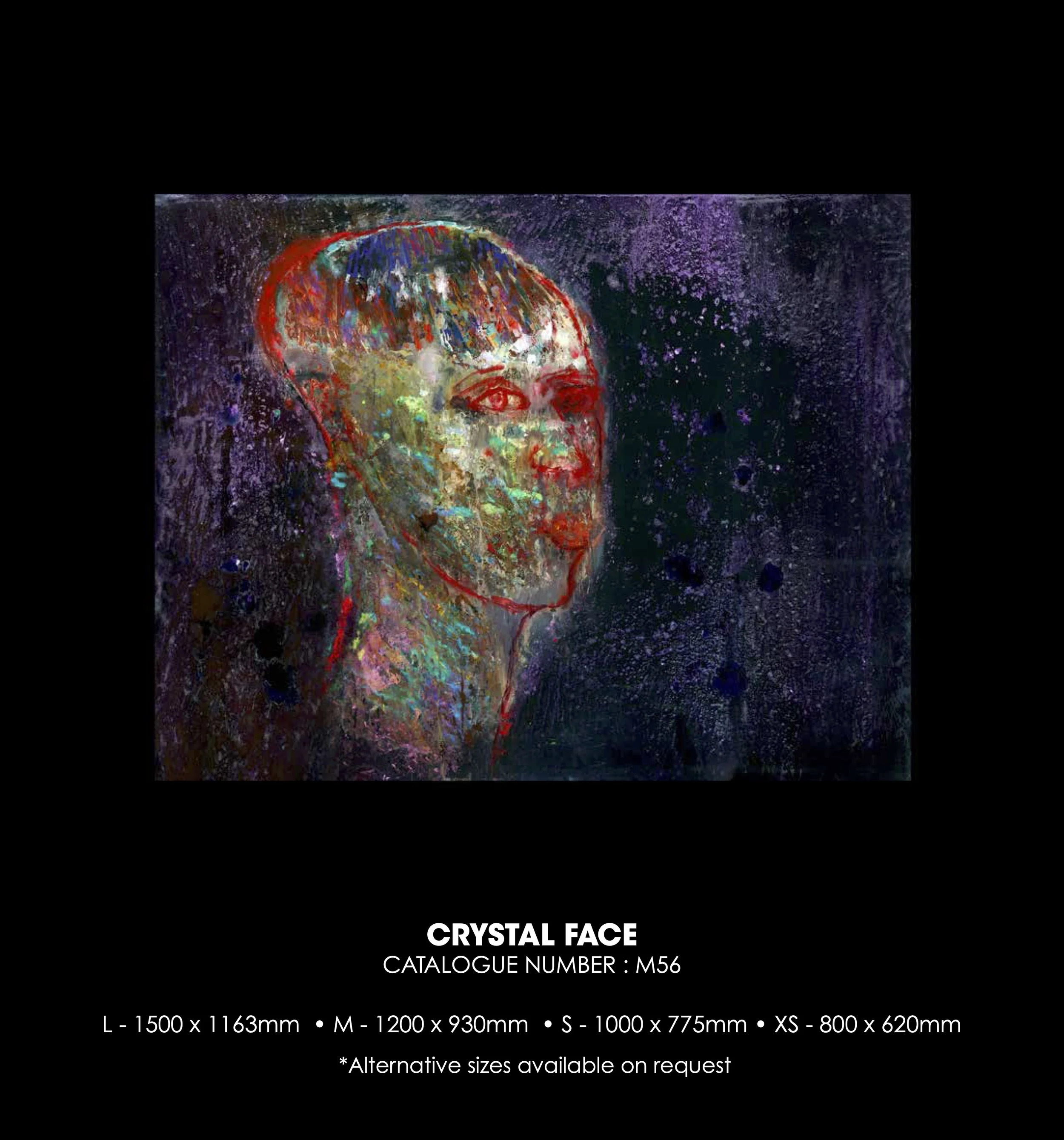

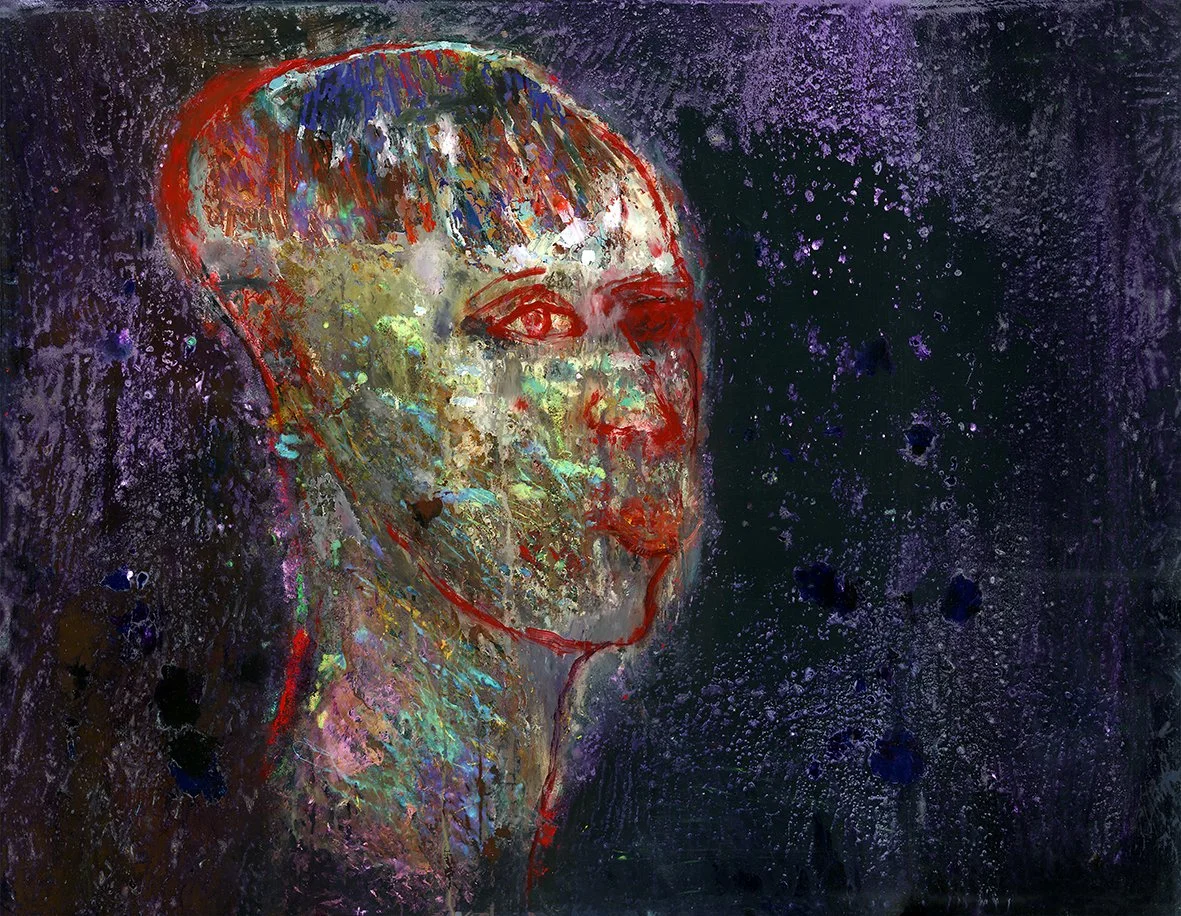

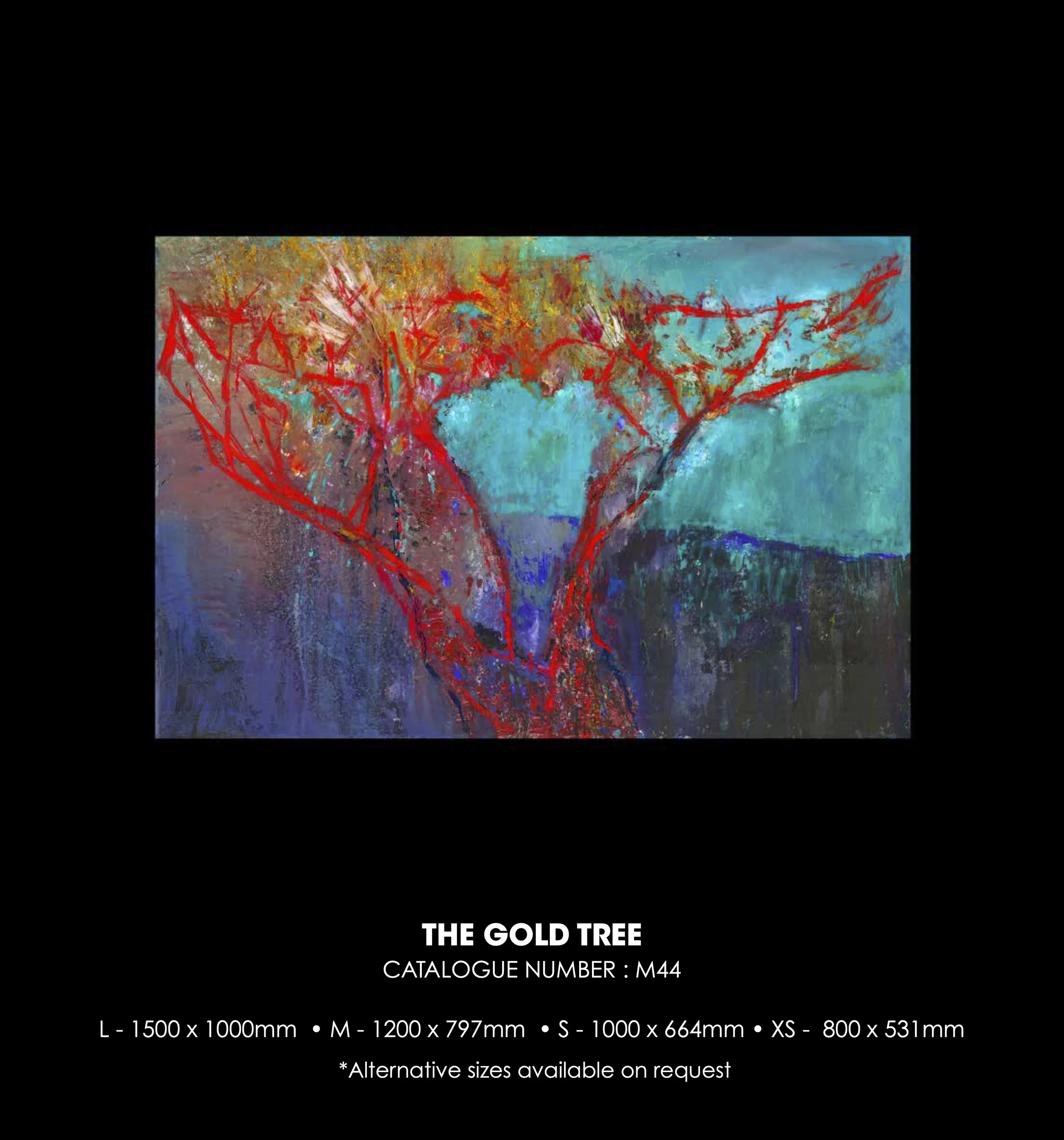

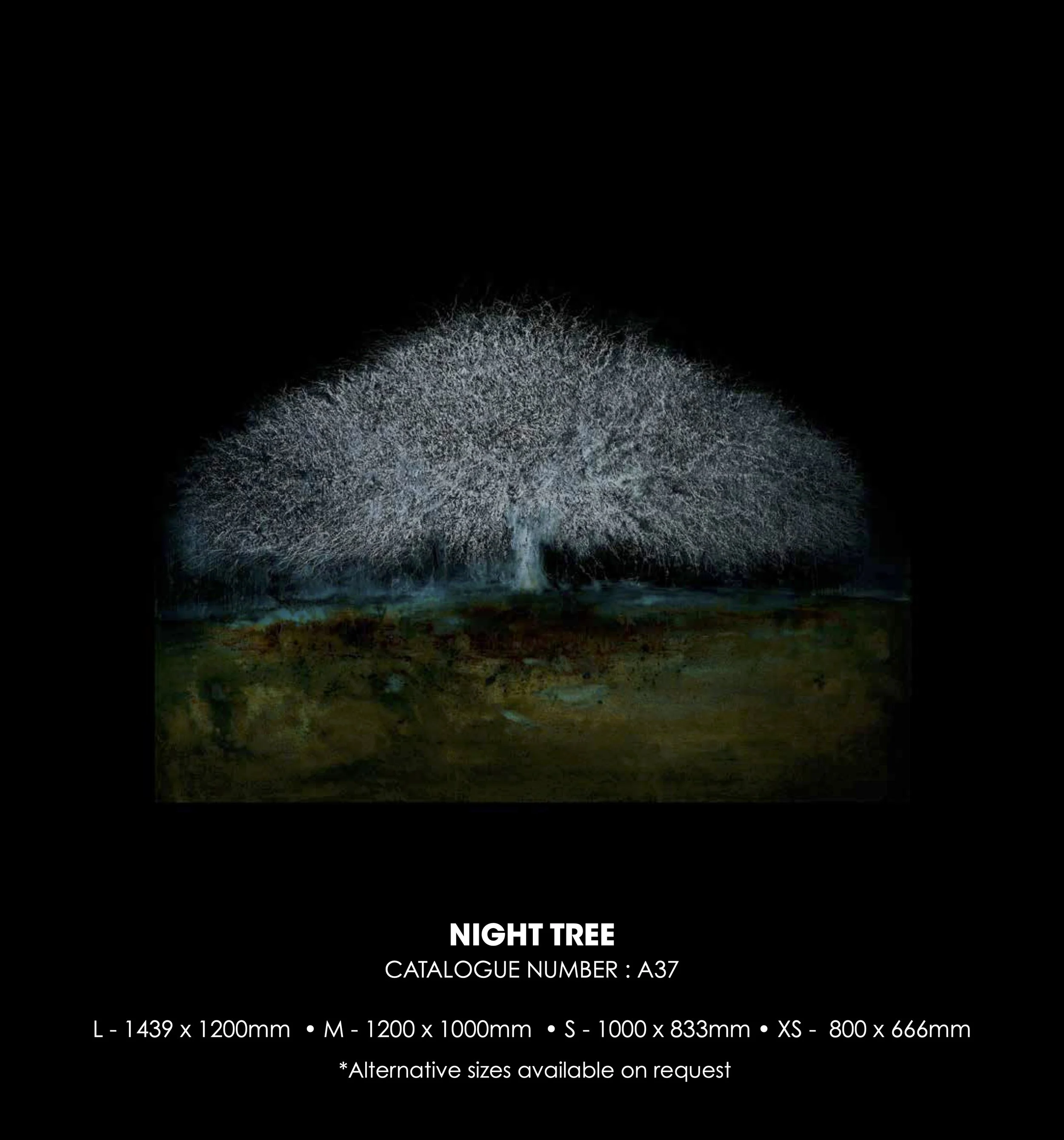

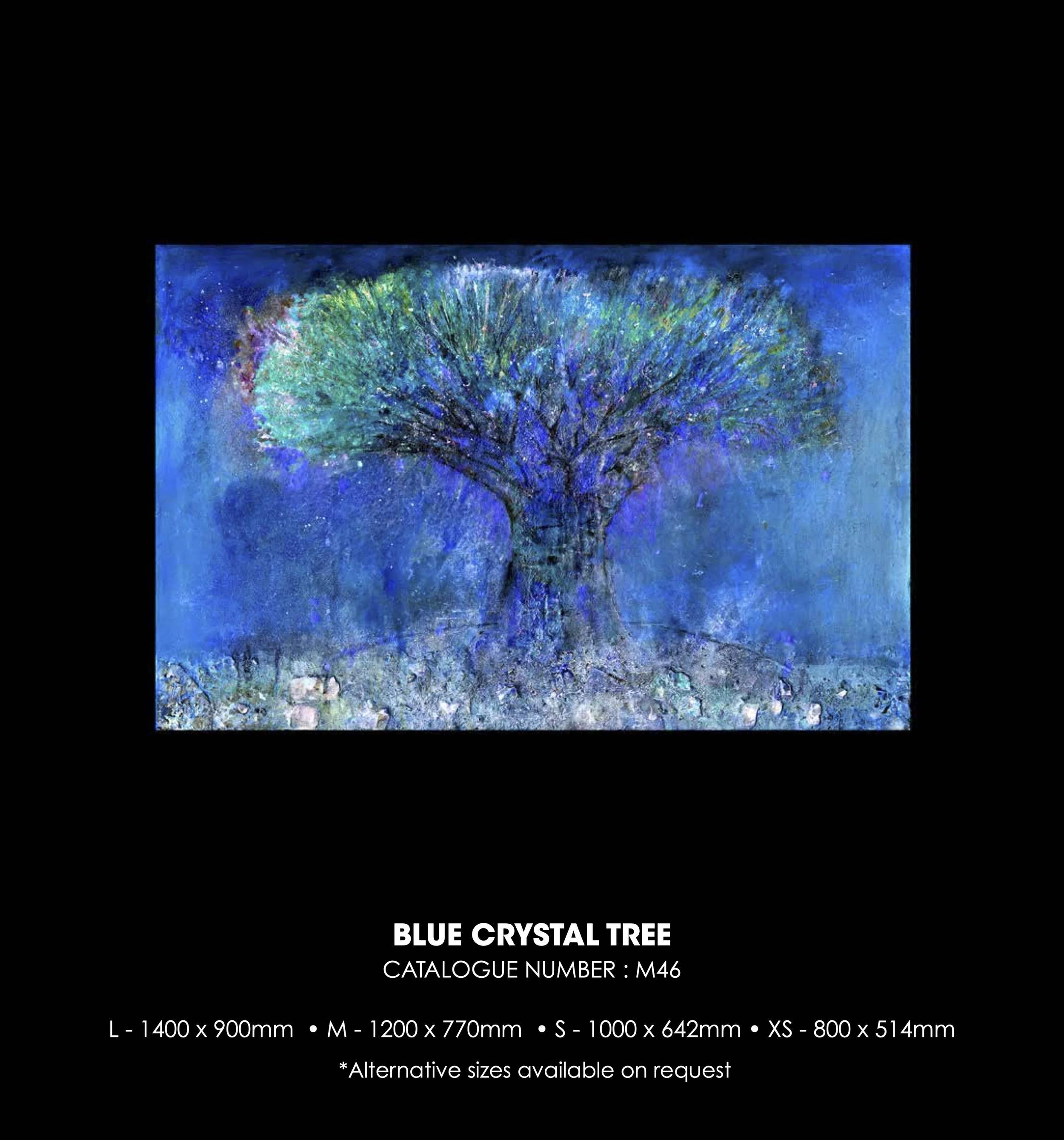

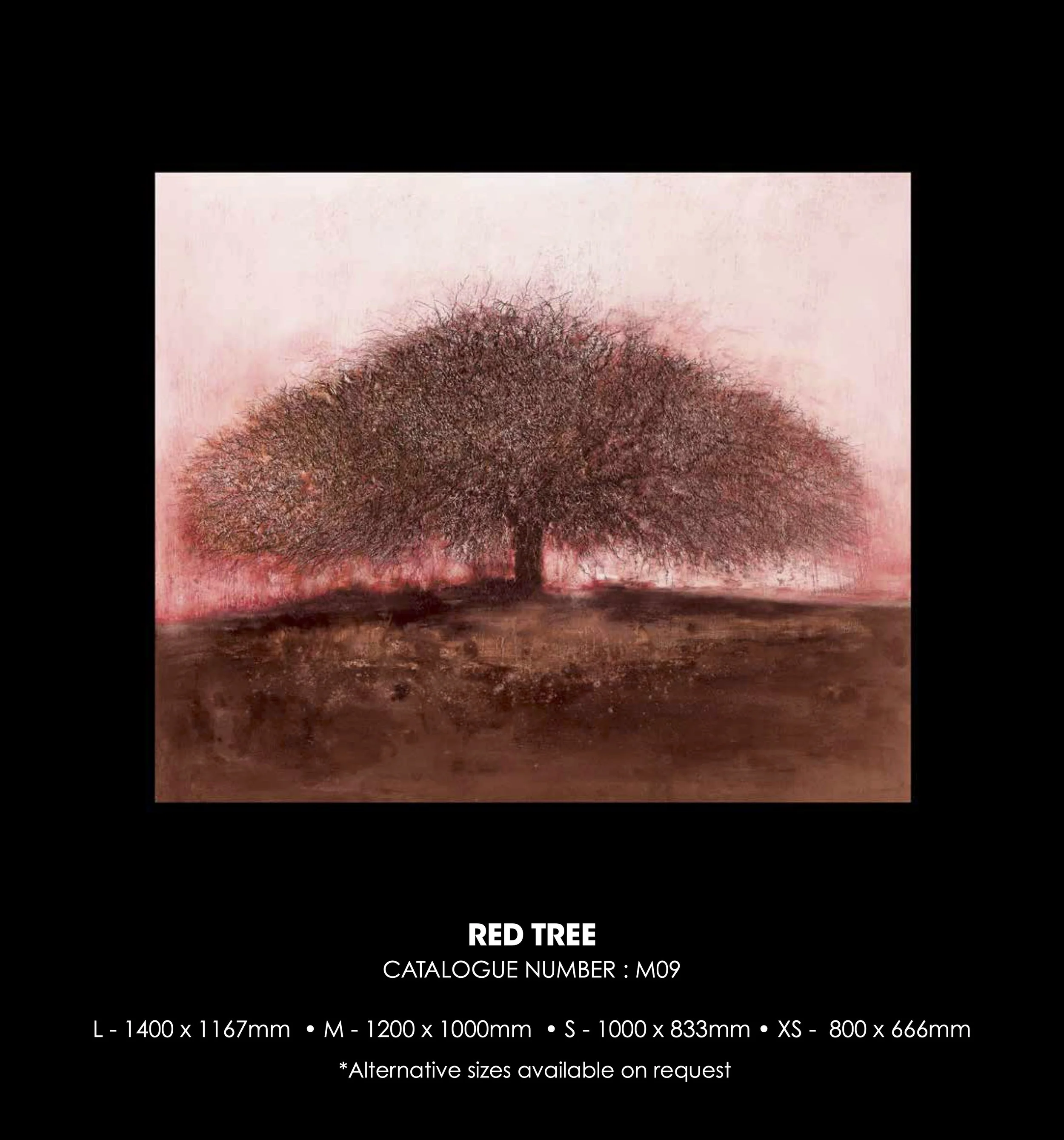

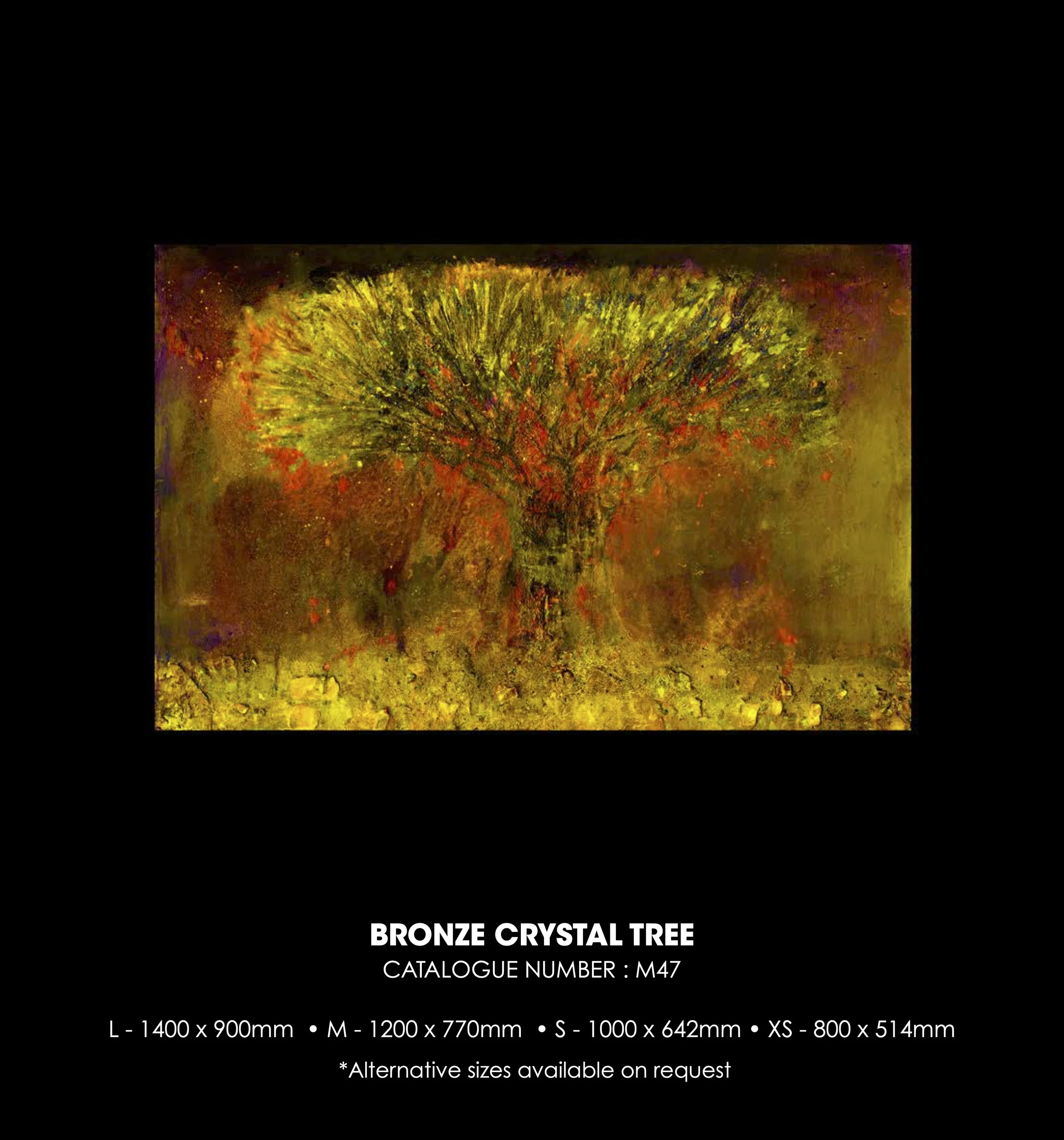

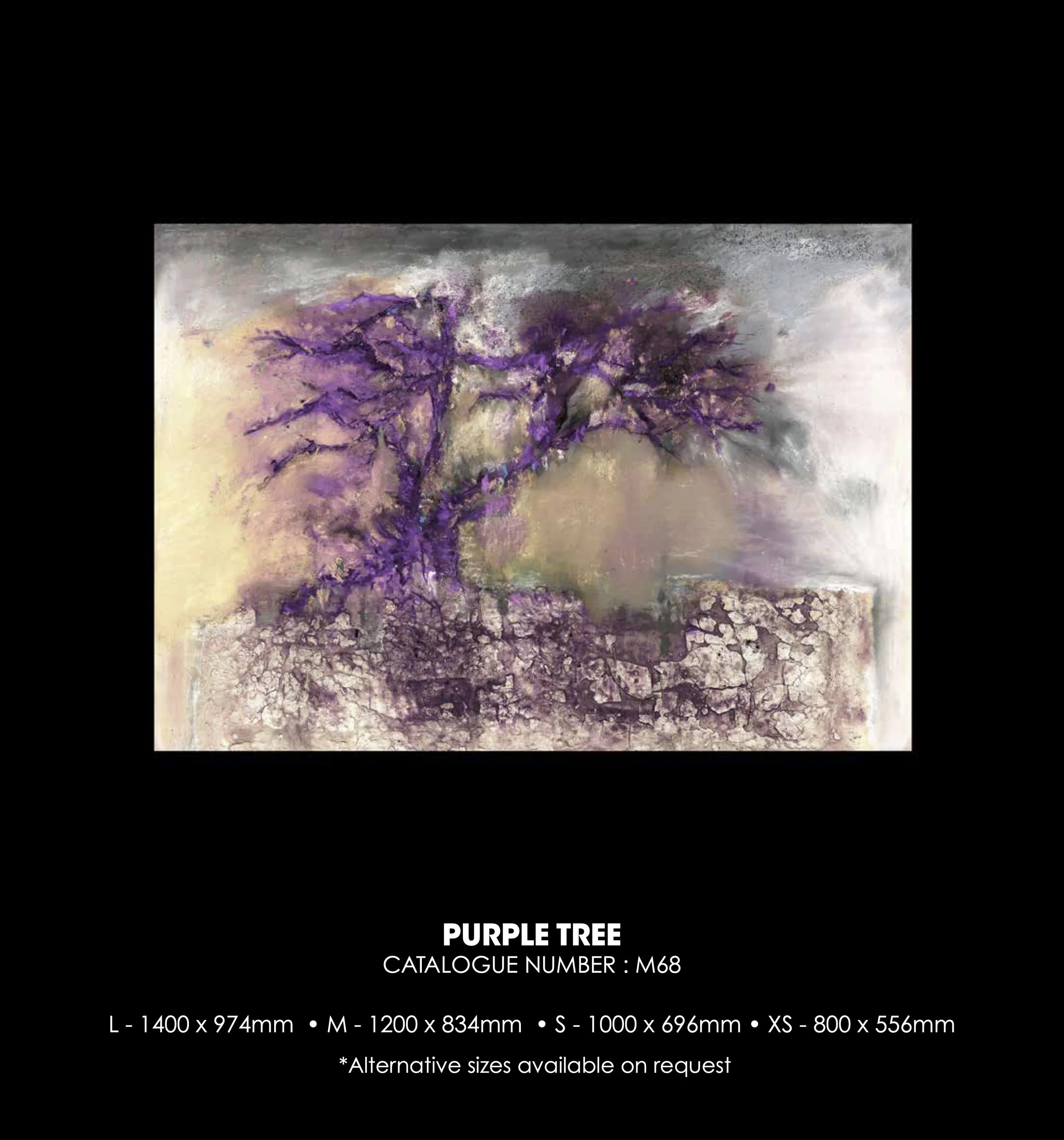

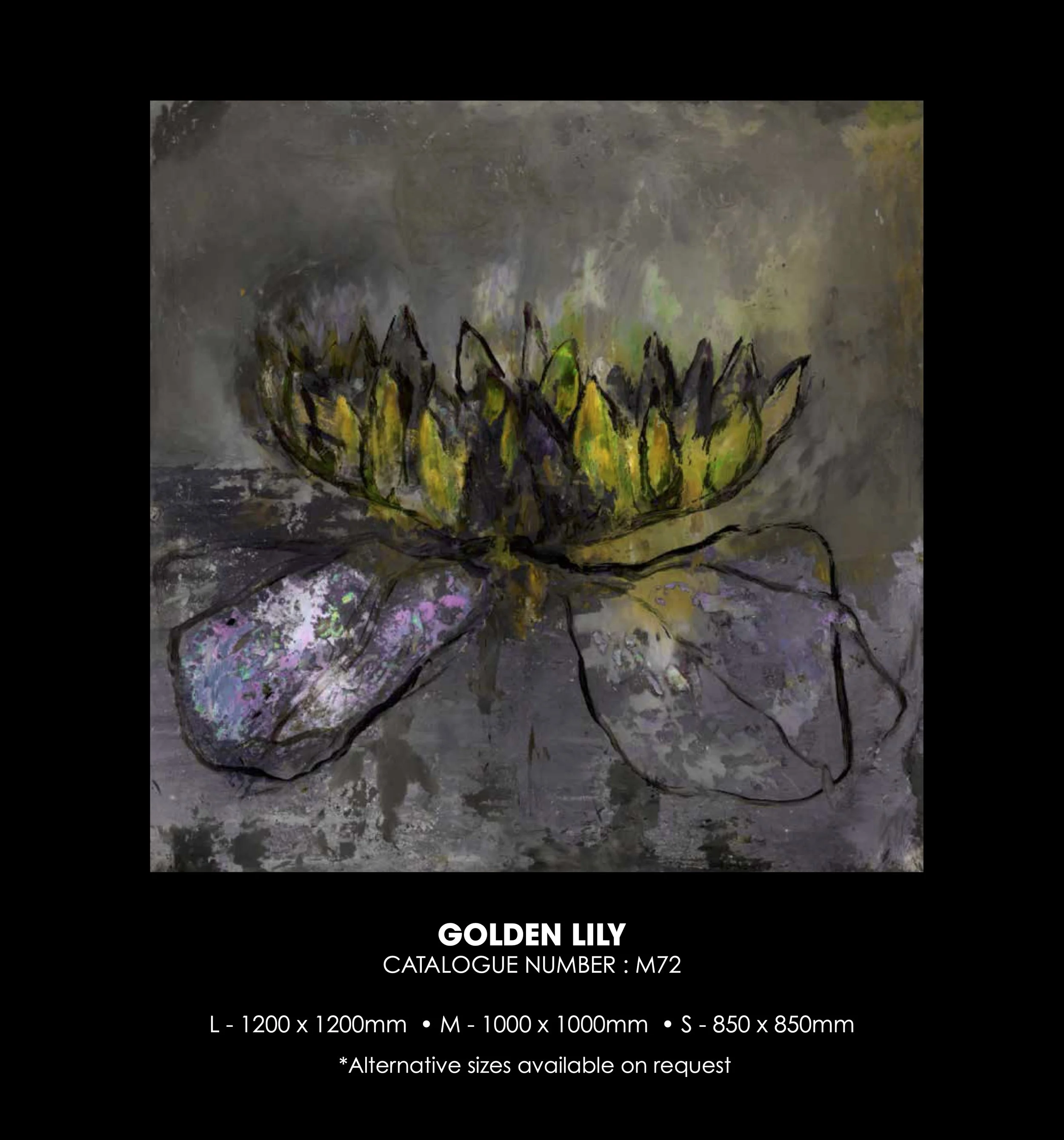

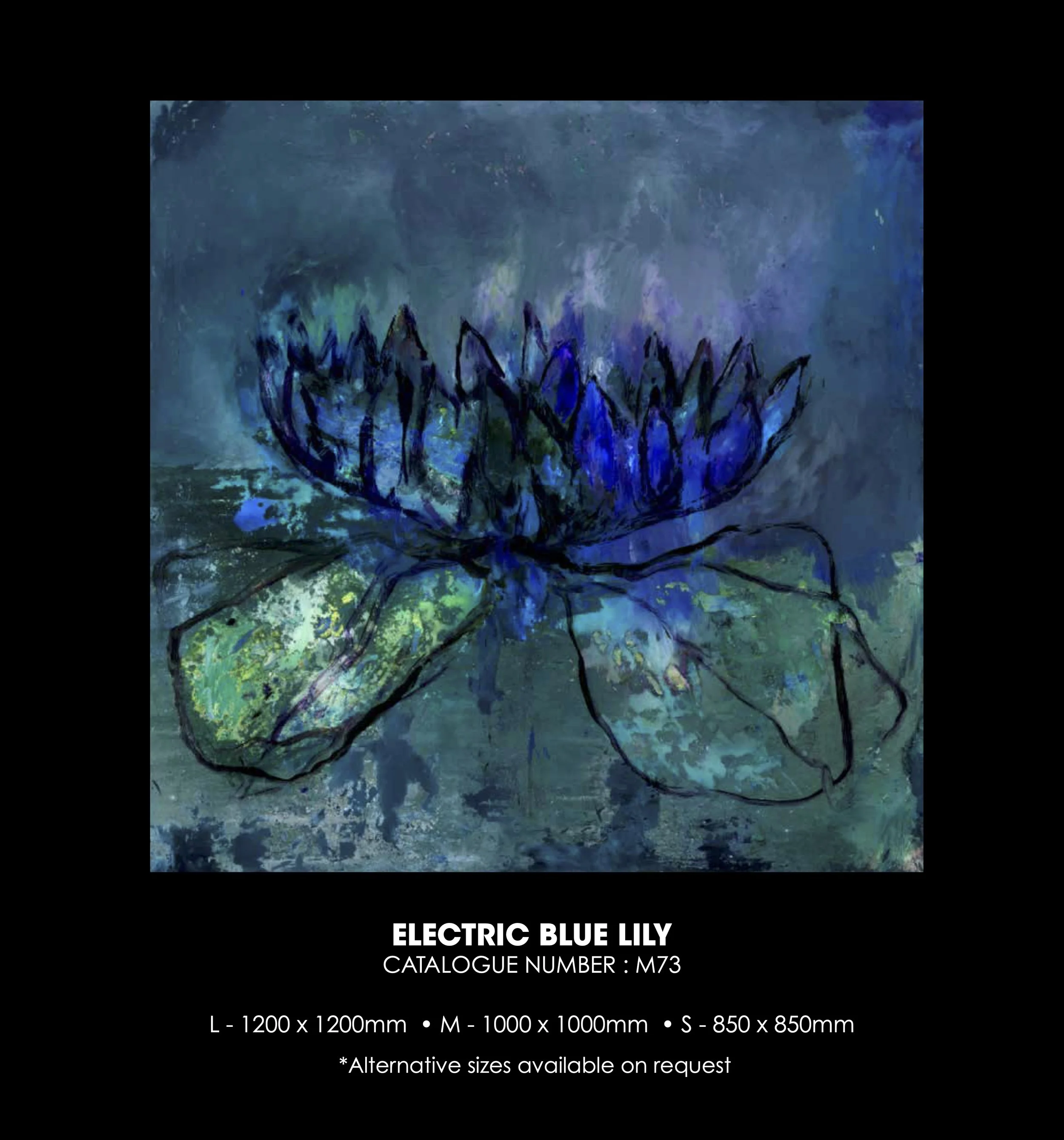

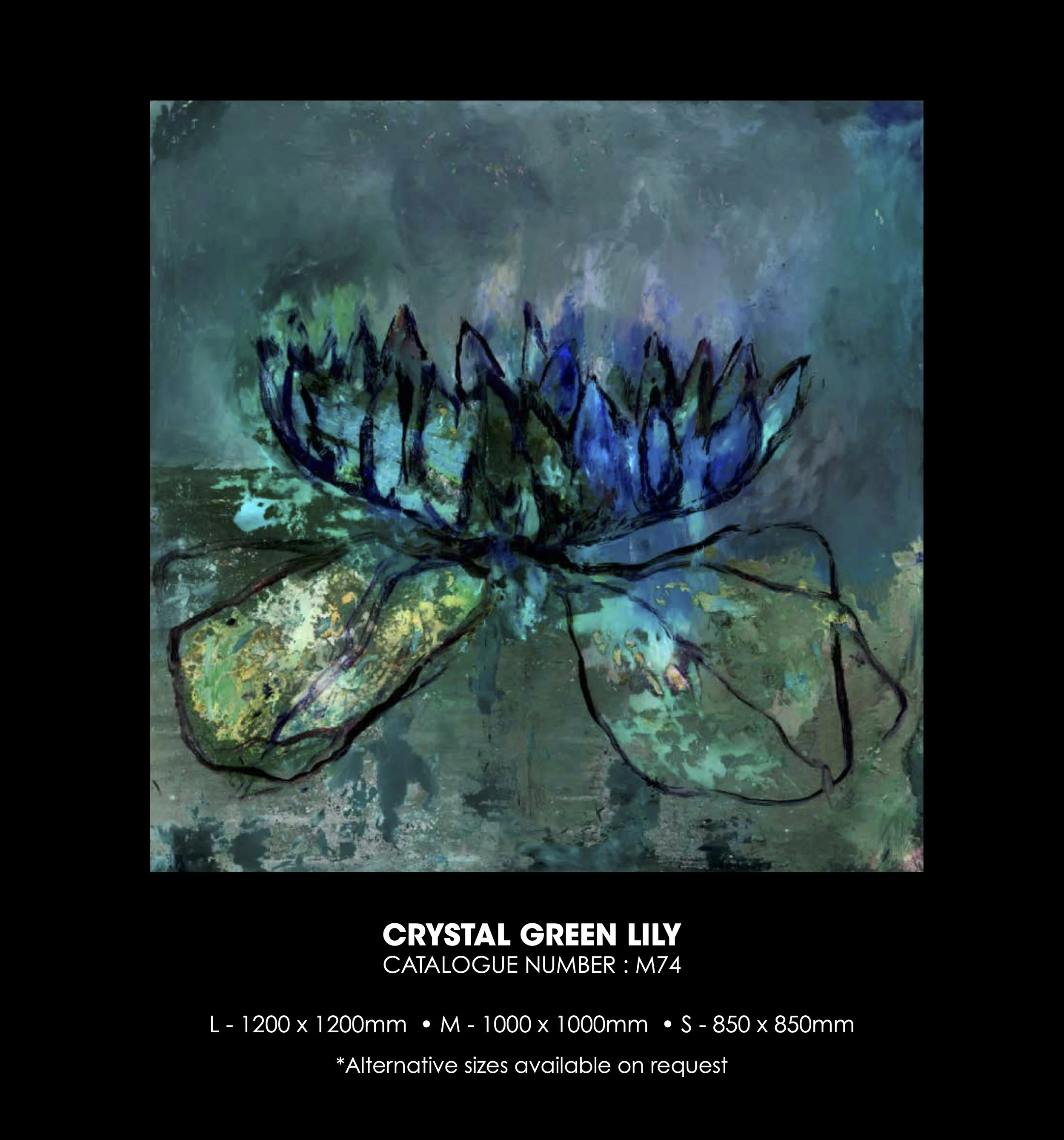

Shop the Collection

Gail Catlin's Diasec Inspired Giclée Series

This collection consists of 37 pieces from the artist herself.

The images have been scanned, with minor adjustments made to match the printing profile. Images are then printed with the highest resolution by specialised inkjet printers using pigment inks.

All prints are printed high quality Hahnemuhle Photorag paper.